Editor’s Note: In our Candidate Forum section, Oakland Report is providing space for candidates for local offices to share their personal stories, motivations for seeking office, and desired policies with voters.

Shane Reisman is a candidate for the East Bay Regional Parks Board

The views that candidates share are their own. Oakland Report does not endorse candidates.

All local candidates are invited and encouraged to submit a view, provided that it adheres to Oakland Report’s editorial standard for reasoned, evidence-based, verifiable information.

There is a parks crisis in Oakland. Nearly 50,000 Oakland residents live nowhere near a park, deprived of the financial and health benefits of green space. I am running for East Bay Parks Director in Ward 2 to pursue an ambitious plan to create access to the vast regional parks system for these residents and provide a lifeline to families in need of relief from the crush of urban chaos.

As a member of the East Bay Parks District, in pursuit of my vision to address long-standing accessibility issues to East Bay Regional parklands, I will advocate for an ambitious land acquisition strategy to connect Oakland residents to East Bay parkland through the District’s extensive Intrapark trail network. My proposal includes Public Education, Land Acquisition Planning and Innovative Solutions. I also call for continued East Bay Regional Park leadership in multi-jurisdictional partnerships to help Oakland benefit from regional economies of scale.

As Mitchell Schwarzer writes in Hella Town: Oakland's History of Development and Disruption, Oakland never fashioned a grand and accessible urban park. Historic opportunities to acquire undeveloped land in the flatlands and lower hills was not seized upon due to “a mentality geared toward business and the individual.” He goes on, “That lack of vision and public service counts as one of Oakland’s lasting failures.” offer a vision and roadmap to address inaccessibility and inequality with a new grand plan to increase access to regional parks starting with areas most impacted by unsafe urban conditions.

An Ambitious Plan

Charles Robinson, 20th Century urban planner, complained of Oakland, “not a spot on all the long bay and estuary frontage where they are free to watch the ceaseless panorama of shipping. And on those hills… no free pleasure grounds to have inalienable rights.” Today, Oakland remains devoid of open parkland as thousands of residents without access to nearby parkland are deprived of the physical, social and financial benefits of living near a park.

The enduring impact of legacy planning has accelerated the consequences of park inaccessibility and the need for a new grand plan. East Bay Parks must exert political leverage and influence as the America’s largest parks district to create and engage in bold opportunities. East Bay Parks was born from a regional mentality and should continue a regional approach on an ambitious scale, such as the District’s leadership in the “Green Transportation Initiative”. This and other multi-jurisdictional organizations provide a model for continued involvement in regional efforts with BART, Oakland, Alameda County Transport, Alameda County, and other East Bay cities.

Today, despite the Agency’s participation in several of these and other high-profile multi-jurisdictional efforts like the Bay Trail Extension, these projects do little to address the most urgent need of many Oakland residents. None of these projects aim to reduce the number of people without nearby park access in priority areas with a high density of low-income households and people of color.

Why does it matter?

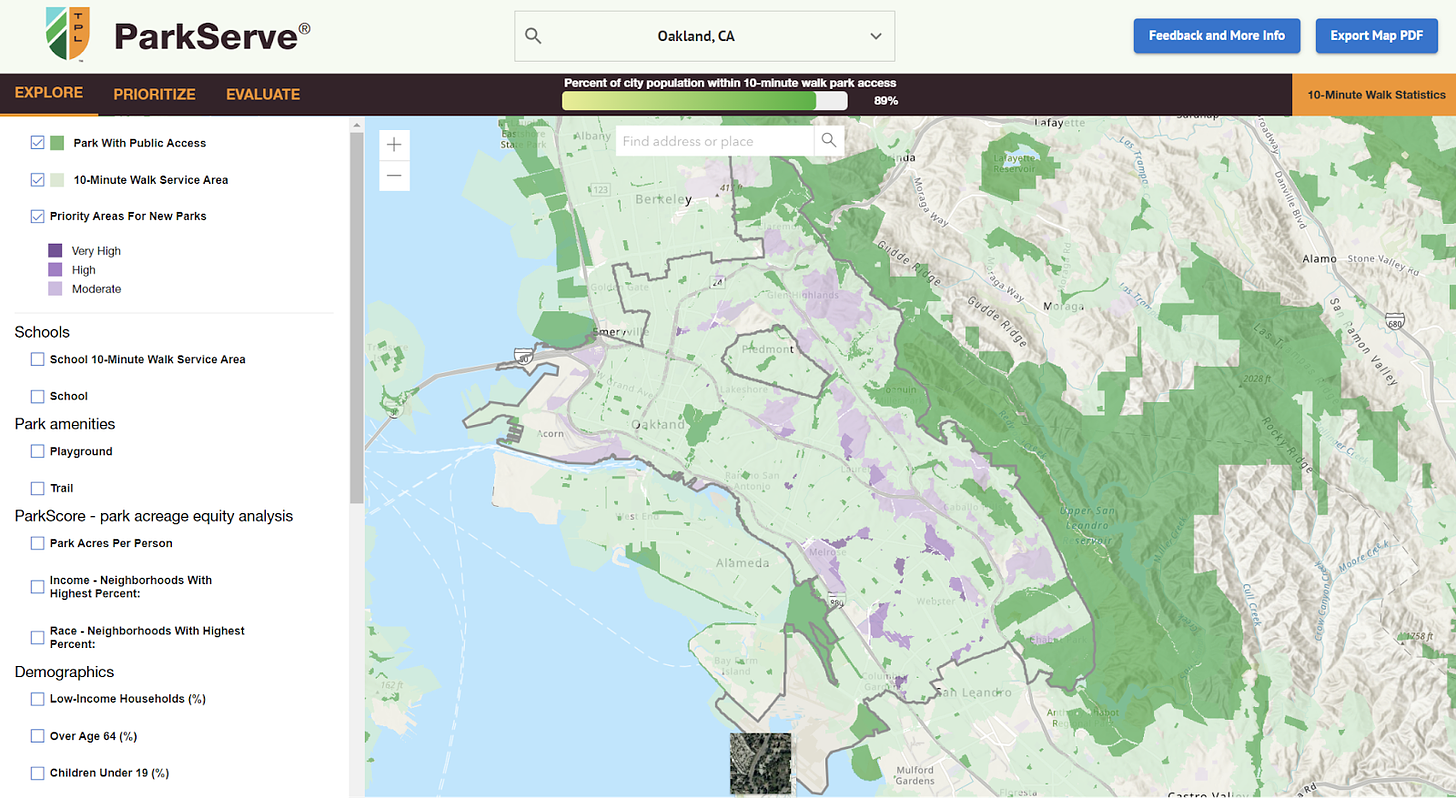

The Trust for Public Lands (TPL) evaluates parks across the country as part of the annual ParkScore index. Scores are based on the percentage of the population within a 10-minute walk to a public park. In Oakland, 89% of people live within a 10-minute walk to a park. But there remain nearly 50,000 people living nowhere near a park. TPL maps priority areas for new public parks to reduce the number of people without nearby park access.

The TPL map above reveals “High” and “Very High” priority areas with a high density of low-income households and people of color. These neighborhoods are also marked by low community health index scores and high pollution burden due to toxic respiratory hazards.

The shortage of access to parks in these areas might also lend itself to a growing body of research that draws a connection between a lack of parks or green spaces and higher crime rates in urban areas. Trends suggest that investment in parks and green spaces could be a valuable tool in reducing crime, particularly in densely populated urban areas.

Several studies support this relationship. Areas with fewer parks or green spaces tend to have higher crime rates, as public spaces can act as hubs for social interaction and community surveillance. A study by the University of Pennsylvania in 2011 found that adding green spaces and parks in urban neighborhoods reduced crime, specifically gun-related violence and vandalism. A Chicago study found that neighborhoods with more greenery experienced reduced levels of violent and property crime.

Further, green spaces improve mental health, reducing aggression and stress, which can lead to lower rates of violent crime.

A study of New York City parks found that neighborhoods with parks had a 12% reduction in crime compared to neighborhoods with fewer green spaces. Research in Philadelphia between 2005 and 2014 showed a 29% decrease in crime around areas that had vacant lots converted into parks or gardens.

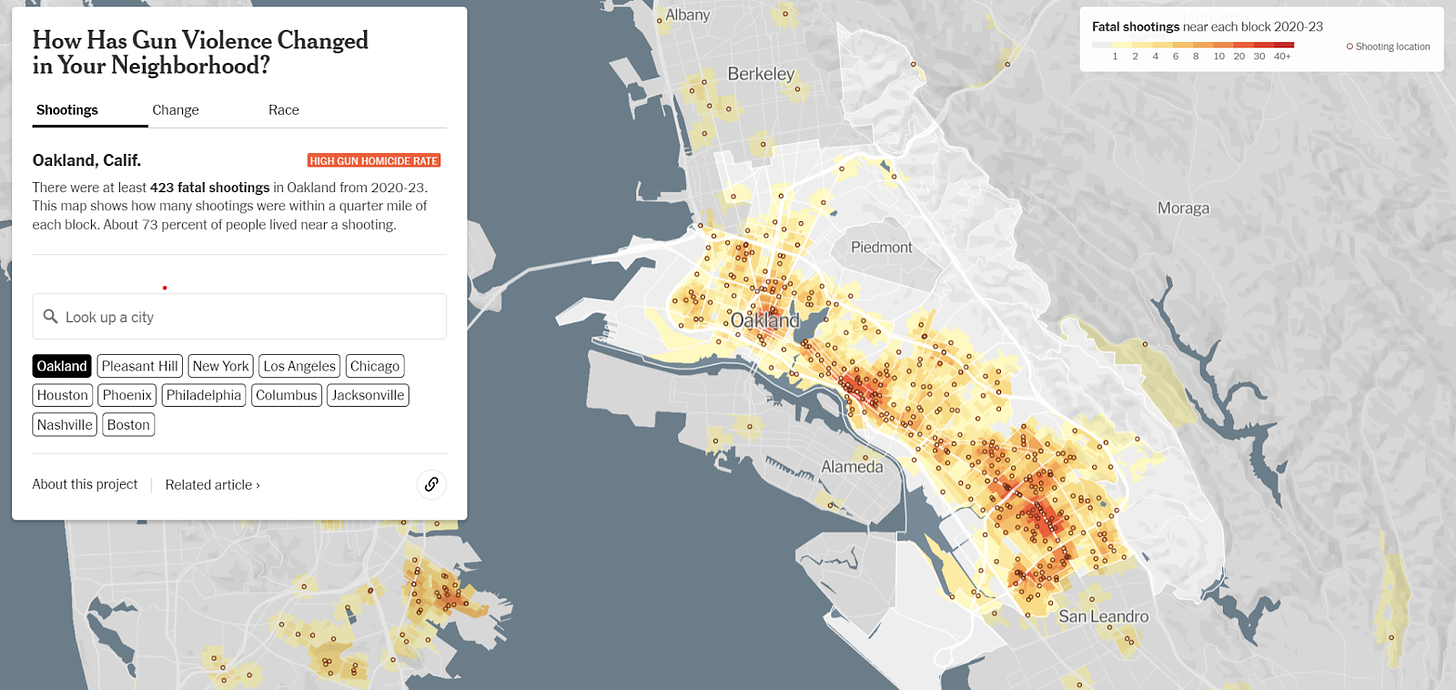

This research is one lens to see a connection between parks and crime, but another is our own experience in Oakland. A recent New York Times analysis provides a snapshot of gun homicide by city. There were at least 423 fatal shootings in Oakland from 2020-23. The map to the right shows shootings within a ¼ mile of each block. About 73% of people lived near a shooting in these areas. The overlay of this gun data with the previous map of priority park development zones illustrate the connection between violent activity in the city and access to park space. Other areas of the East Bay do not as clearly illustrate the relationship between violent gun crime and park access.

How did we get here?

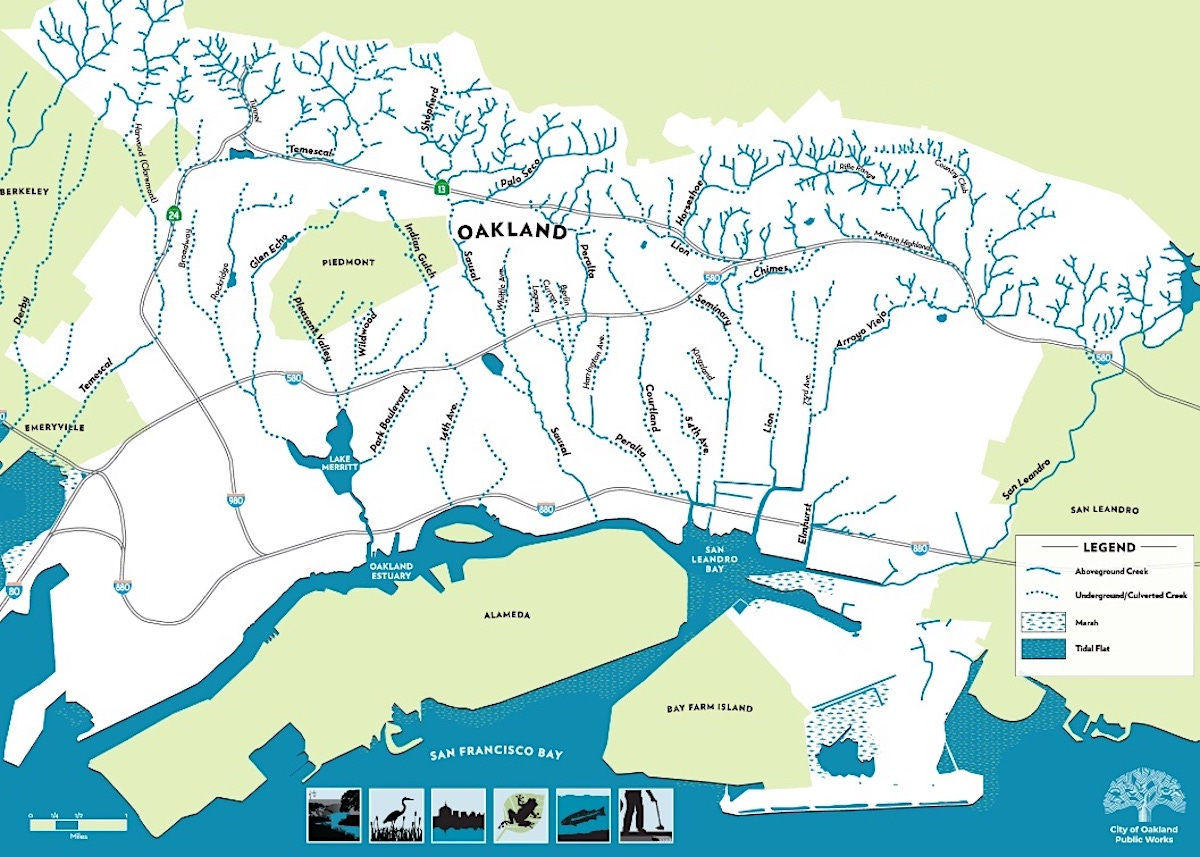

According to Schwarzer, before European settlers arrived in the area, dozens of creeks branched down from Claremont in the North to San Leandro Creek in the South. They snaked from the Redwood Groves in the upper hills down and across the flatlands, meandering across the marshlands to the Bay. To take advantage of this natural landscape, early city designers envisioned a great park wrapping around Lake Merritt, up the bluffs to the east and what’s now Trestle Glen. The groves of Eucalyptus and Oak, then popular for picnicking and hiking, would further extend through the narrow Dimon Canyon, up the ridgeline and into the old Redwood Groves.

Despite these early best intentions, park development removed land from tax rolls and as subsequent administrations took hold at City Hall, priorities shifted away from land acquisition for parks. Further, around Oakland, like in Los Angeles and other western cities, previously undeveloped terrain was abundant nearby so the need for parks was more easily dismissed.

In the ensuing years, voters approved the acquisition of the East Bay Water Company and its 40,000 acres of watershed, dams and reservoirs. The acquisition encompassed 10,000 acres of surplus land and in1934 voters approved formation of the East Bay Regional Parks to administer the land. Key acquisitions in the early days included what are now the regional parks at Tilden, Sibley Volcanic Preserve, and Lake Temescal. From the start, parks like Temescal, Roberts and Chabot, were intended to serve as substitutes for city parks lacking in Oakland.

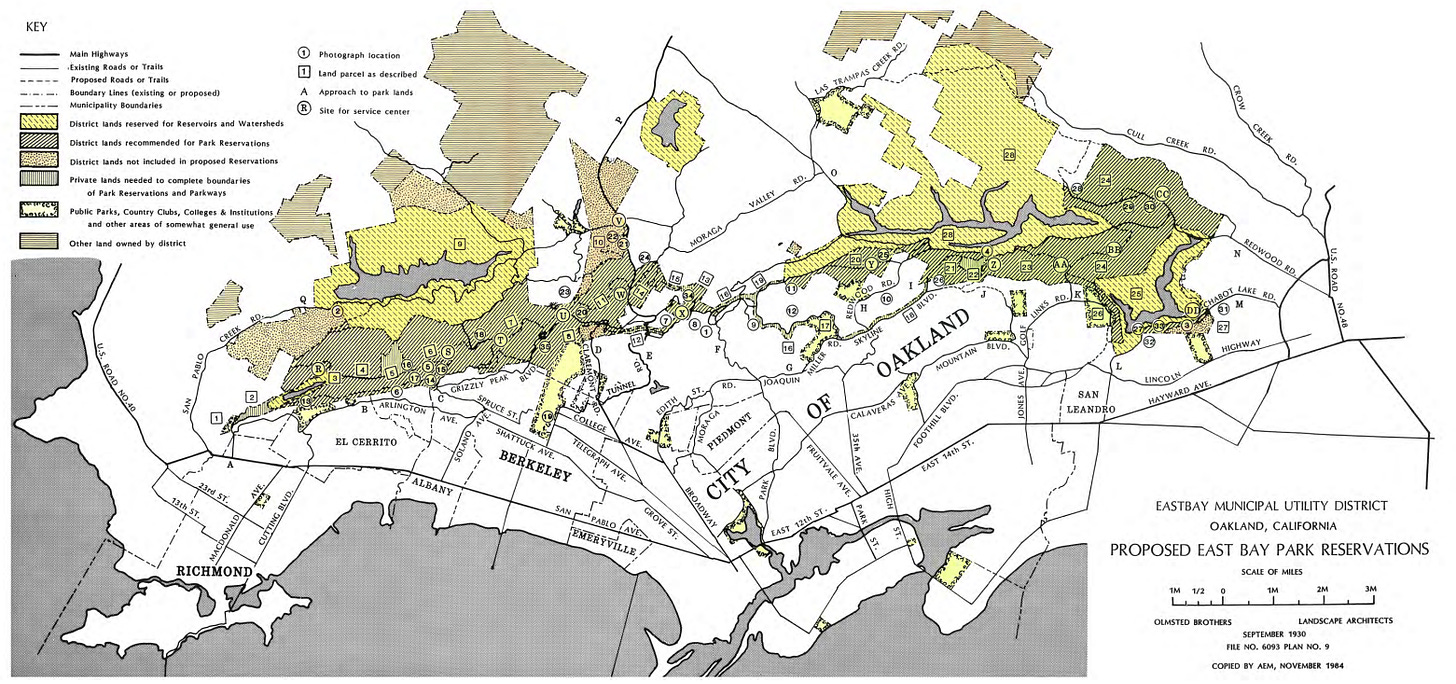

Most new East Bay regional parks were concentrated along the local watershed, and primarily planned as destinations accessible by car. The new parks cut and intersected dedicated vehicular pathways to new parts of the East Bay, often at the expense of municipal park development in Oakland. The map of the original 1930 park planning material place East Bay Parks in and around Oakland in locations hard to reach for those without cars.

A Bold Plan Forward

Today, in the city of Oakland there remain islands of residents with no easily accessible parks. These areas struggle with increased crime, low community health scores and high pollution. Since its creation, EBRPD has grown through acquisition to 125,000 acres, yet current maps reveal that these disparate islands are remnants of earlier decisions restricting park access and outdoor options and their benefits to a community.

The impact on low-income Oakland neighborhoods or neighborhoods of color is striking. In Oakland, residents of lower-income neighborhoods have access to 78% less nearby park space than those in higher-income neighborhoods. Residents in neighborhoods of color have access to 69% less nearby park space than those living in white neighborhoods. An ambitious East Bay Parks plan to address these disparities and demonstrate Oakland’s commitment to access, and equality can seek to address these disparities.

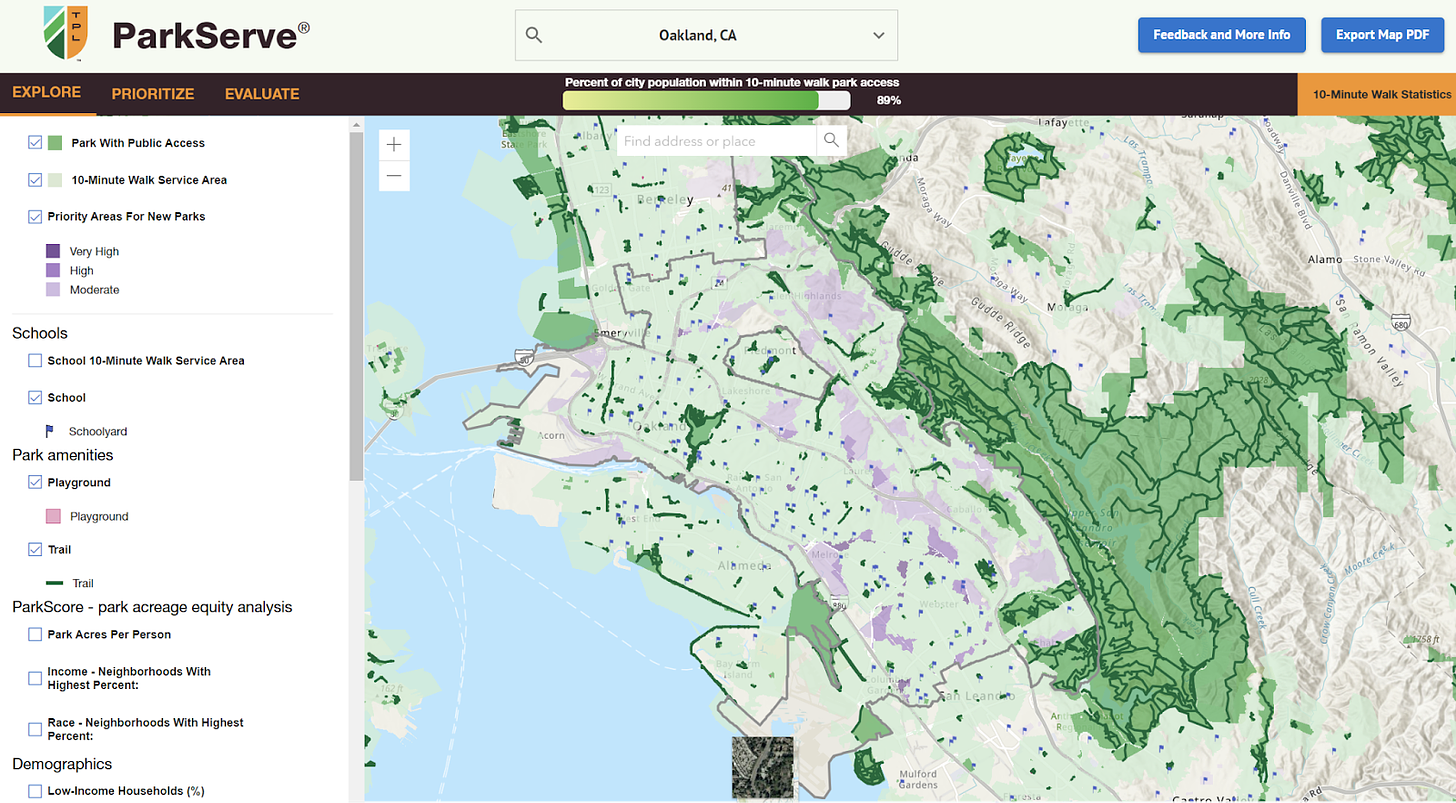

Park inaccessibility and inequality present the need for a new grand plan to increase access to regional parks in areas most impacted by troubling and unsafe urban conditions. The map below shows priority park development areas and green lines illustrate existing trails branching out across existing parkland. These lines represent pathways that can combine strategic land acquisitions, trails and pedestrian right-of-way, to bridge disparate parts of the East Bay.

A plan to connect these neighborhoods will require a multi-thread effort focused on 1) Public Education, 2) Land Acquisition Planning and 3) Innovative Solutions.

1. Public Education

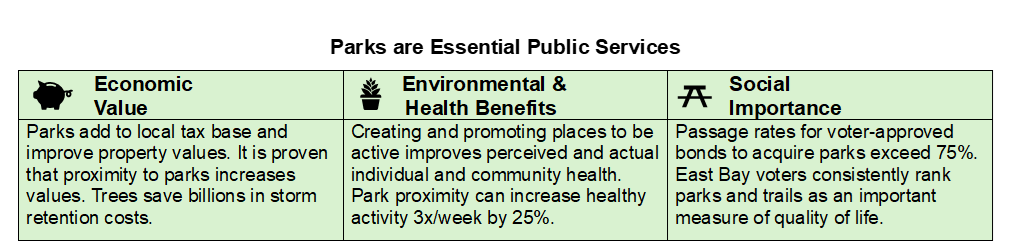

A public education and advocacy campaign to build support for a massive park expansion must focus on raising awareness about the potential benefits to the community. The campaign will emphasize the importance of green spaces for public health, recreation, and public safety. By highlighting positive impacts, the campaign taps into community values around economic well-being and opportunity development.

Engaging residents through informative workshops, social media and collaboration with community leaders is vital. Storytelling showcases testimonials from families and who frequent parks for leisure, exercise, or social interaction. Visual elements like infographics and videos can illustrate the potential transformation, making the vision more tangible.

Audiences for the public education campaign include residents, families, environmental advocates, community leaders, school groups, and business owners. Engaging diverse populations fosters support and targeting individuals interested in health, recreation, and sustainability will encourage broader involvement.

Additionally, the campaign should address potential concerns, such as maintenance and funding, and present solutions showcasing the park's role in boosting local economies by attracting more visitors. Partnering with schools, local businesses, and environmental organizations to amplify the message.

2. Land Acquisition

A successful Land Acquisition planning strategy for a massive park expansion requires a comprehensive approach that balances community needs, environmental considerations, and budget. We will begin with a thorough assessment of available land and potential sites that align with our vision. This includes underutilized areas, vacant lots, and environmentally significant lands that could enhance ecological diversity.

Efforts to capture and carefully document community input is essential. Public forums and collaborating with stakeholders—such as city leaders, landowners, and environmental groups—will help gather input and build consensus around land acquisition goals, drive participation, foster trust and encourage support.

Financing the acquisition is another critical component. Exploring multiple funding sources, such as government grants, public-private partnerships, and donations, will provide necessary capital. Leveraging the land trust can protect acquired spaces from future development.

Legal and regulatory considerations will be vital; ensuring compliance with zoning and environmental regulation. A phased approach may be beneficial, allowing flexibility and adaptation as opportunities arise. This strategy will create a well-planned, sustainable approach that enriches the community and preserves natural resources.

Case Study

Oakland’s creeks once flowed free from the hills to the Bay. What’s their future?

The Rockridge-Temescal Greenbelt turns a 2000-foot stretch of Temescal Creek culverted creek bed between Hardy Park and Redondo Playground into a rich neighborhood asset. In Hardy Park, at the upstream end, is a large grate over the culvert where you can stand and listen to the water.

Local partnerships working to “daylight” underground waterways include Friends of Sausal Creek, Friends of San Leandro Creek, and East Bay Native Plant Society.

3. Innovative Solutions: Complex, competing interests of an effort of this scale requires commitment and creativity. One innovative effort demonstrated by committed Oakland community leaders is recent projects to restore urban streams. Streams that were buried in tunnels underground have been “daylighted,” allowing them to revert to a more “natural” state. The City of Oakland and Alameda County assist in stream restoration projects to steward and build watershed communities.

Andrew Alden, author of Deep Oakland: How Geology Shaped a City, this labyrinth of underground waterways is now exposed to daylight for the first time in many years. Many of the creeks now underground, run through neighborhoods, parks, and commercial spaces where they cannot often feasibly see the light of day. Additionally, these streams run through different neighborhoods and communities, each with a unique perspective and connection to the watersheds. These efforts reflect a thoughtful, detailed approach to creating new pathways based on early local waterways.

I for one do not support acquiring more land for parks. Oakland has many parks in the D3 district, they are neglected and hotspots for crime. They look blighted. The east bay and Oakland have no muscle to maintain parks. Compare this to the parks in San Francisco, they are beautiful.

It would be irresponsible to hand over more land to organization that has not managed parks well.

I would instead advocate for divesting park land to developers with a promise of maintaining some puiblic space. The current situation in D3 is atrocious. Parks cause more harm to the community than not.

An easier fix would be to have public transit service to the already well-maintained EBRPD parks. A weekend-only bus to Redwood Regional Park would be amazing. I agree Oakland can’t maintain the parks it has now. Joaquin Miller is a tinderbox of dead trees.