Oakland leaders perpetuate misinformation to justify public safety cuts

Oakland's council, city administration, and labor leadership are locked in a game of misinformation to advance their narrow interests. It may result in total fiscal collapse.

Oakland’s structural deficit is $115 million this year, with the city projecting an additional $130-150 million shortfall next year. The crisis is no surprise. The city administration and council have avoided fiscal discipline for years, repeatedly using one-time sources of cash to plug the ongoing deficit. But now the city has used up its one-time maneuvers and federal rescue dollars. It will face bankruptcy in months, unless drastic cuts are made by December 31, 2024. City leaders are angling to do this with further cuts to overstretched public safety departments.

A podcast summary and discussion of this article is also available.

Rather than tackle this crisis with sober and urgent pragmatism, the city administration and council leaders are playing a misinformation game that seeks to protect administrative and social service spending and selected interest groups, at the cost of diminished public safety services.

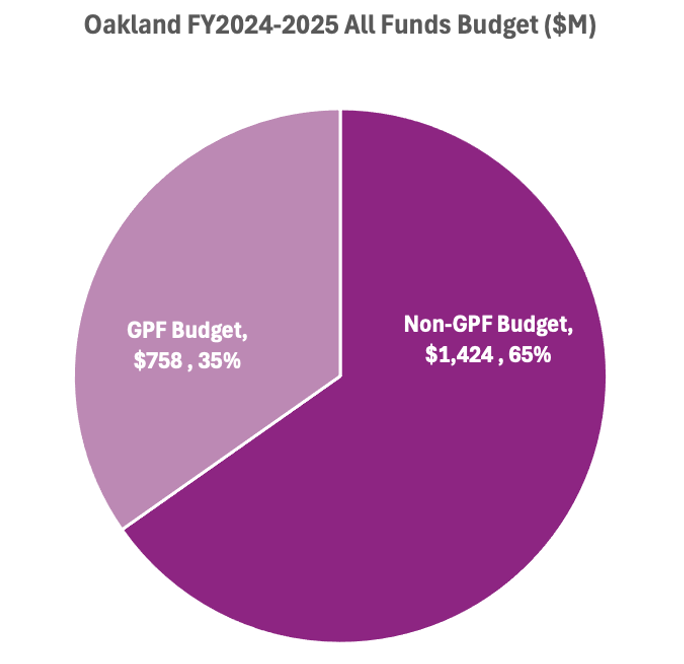

The city administration and council misleadingly proclaim that Oakland’s public safety spending is more than 60% of the budget. But it actually comprises just 25% of the city’s overall budget. The falsehood is based on a simple deception: the city operates two budgets and city leaders are only talking about one of them—the budget that funds police and fire. But they do not account for the second one that funds non-safety services.

Police and fire are funded almost exclusively from that first budget, the General Purpose Fund (GPF), which is the unrestricted fund. Those services comprise 65% of $758M GPF budget. Conversely non-safety departments are primarily funded out of the second budget—the $1,425M restricted funds budget. Non-safety activities consume 97.5% of those restricted funds.

Council members have exploited public misunderstanding of these two budgets to aggressively cut public safety services over the past five years. Since 2020, the city council has cut 347 fire and police positions, despite an increasing demand for their services. Now they are suggesting public safety needs to be cut even further. Yet they have left budgets in other departments virtually untouched during the present fiscal crisis, and in most cases have even increased them.

These choices are motivated by a combination of ideological doctrine and transactional politics, and justified by a set of core myths promulgated by city and council leaders. We detail and correct those myths in this article.

Public safety is not the only service a city must provide. But it is the most essential one—the very foundation of a civil society and a growing economy. To unduly sacrifice it in the name of ideology or political paybacks is a choice that could amplify Oakland’s safety crisis and exacerbate its downward economic spiral.

After years of denial, Oakland’s budget reckoning has arrived

For the past four years the council has demonstrated no will to stop the city’s obvious overspending problem. Now the bill has come due.

Bradley Johnson, the city Budget Administrator, made it even more clear in his remarks to the city council on November 19—the city is within months of total fiscal collapse. Mr. Johnson ended his statement with a plea:

“Councilman Gallo, you have asked on repeated occasions from us to let you know when it is critical that we take action. I want you to hear clearly at this dais that we must take action over the course of the next month and a half to preserve our solvency.

I want to make sure. I want to make sure that that is very clear.”

The city faces a $115M deficit this fiscal year (July 2024 to June 2025), and is projected to face a $130-150M deficit next fiscal year. Without drastic and immediate spending cuts, the city will become insolvent and forced to enter federal bankruptcy.

The operative words here are spending cuts—there is nothing the city can do at this point to solve the problem with new revenues (taxes, grants, or relief funding). Revenues take years to build, but the fiscal cliff is here and now. The city made severe cuts to public safety in its October 1 contingency budget, but those appear either too slow or too little. It needs to enact more aggressive cuts by December 31, 2024.

Why this urgency?

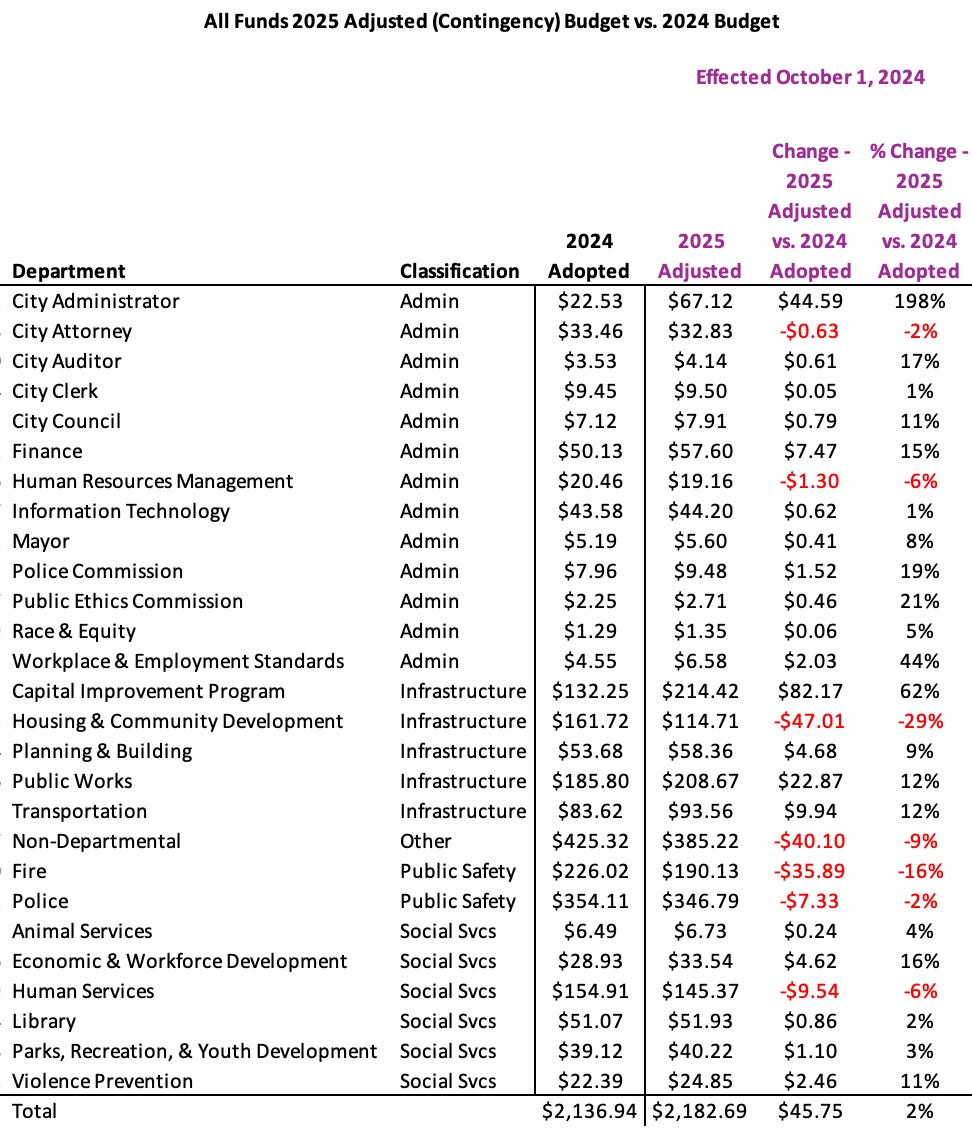

The city chose not to make the needed reforms to its budget in 2023, or this spring, or in the years before when it ran large structural deficits that were repeatedly called out by the city finance department and the Budget Advisory Commission. Even though it limited public safety spending (an 11% real dollar decrease since 2020), it let administrative and social service spending balloon by 62% (31% real dollar increase). And it gave above-inflation wage and pension benefit increases to all city employees.

Now all operating fund balances (the city’s surplus funds from prior years) have been spent, including the $93M General Purpose Fund balance, the $11M Vital Services Stabilization Fund balance that existed at the start of last year, and nearly half ($33M) of the $70M of emergency reserves intended primarily for natural disaster response.

Characteristic of the council’s denial of the problem, it hasn’t even approved spending against the emergency reserve funds. The city is presently borrowing cash from other restricted funds (like pension trusts and housing funds) under the assumption it will get authorization to access the emergency reserve funds before year end.

But the game of IOUs has a limit. The city has only $37M of emergency reserve cash left, not enough to escape a reckoning for another year. And because the city waited half the fiscal year to begin making cuts, it has only 6 months to accrue the savings needed to balance this year’s budget. Basically, that means the city will have to cut twice as much as the annual cost of any line items—because they will only save half of the annual cost. In terms of staffing, that means cutting two jobs to save the equivalent of one person’s compensation costs.

If the city delays the hard decisions any further there will not be enough time to accrue the necessary savings. Insolvency becomes unavoidable.

Will city leaders finally make the necessary spending cuts? Or will they continue to deny the reality that Oakland faces imminent bankruptcy? If they do act, will they prioritize the best interests of Oakland residents, or placate narrow interest group demands?

How is the city council responding?

Listening to council member pontifications in last week’s meeting, one would get the impression they were blindsided by this situation—that external forces are at work, making them more the victims than the actors who directly approved excess spending. Council President Nikki Bas listed four different reasons why it wasn’t their fault:

“Across our region, the state, the country, we are seeing other cities grapple similarly with deficits. We are here because of higher interest rates, because of overspending in a limited number of departments, as well as long term disinvestment from the federal government around safety net funding, as well as California's Prop 13, which voters tried to improve in 2020 but we fell short “

It’s a speech she’s made several times throughout the ongoing budget crisis—pointing fingers at interest rates, the prior mayor, and capitalism itself—while the city continues to speed toward fiscal collapse under her present leadership.

As the Council President and leader of the majority progressive caucus in the council, she never took action during her six-year tenure to correct the underlying fiscal issues. Her inaction is not for lack of awareness. The city’s finance department has been issuing stark warnings of the $100M+ structural deficit for five years. To date, her most aggressive budget action, outside of advocating for cutting police spending in half, seems to be an attempt to suppress public awareness of looming bankruptcy.1

Rather than address the deficit, Bas and the council chose to spend $225M of one-time COVID relief money and the city’s reserves to plug deficits caused by large jumps in social service spending.

And now, even with bankruptcy looming, city leaders have shown no indication of changing course.

Willful misinformation

How do council members aim to resolve the crisis?

The answer lies buried in Bas’s opening statement at last week's council meeting. She used coded language to call out overspending by “a limited number of departments.” What she actually means is “the fire and police department.” And she makes that clear later in her remarks:

“Specifically, given that public safety expenses are the majority of the general purpose fund budget, what specific measures have been put in place for OPD as well as for fire?”

She and other council members have used every recent discussion of the budget to argue for reductions in public safety spending, and in particular the police. Fire and police are the go-to villains in the narrative city leaders like to construct—until, of course, they need a wildfire extinguished, a sideshow suppressed, or the Ceasefire program properly activated.

Throughout the meeting, the city administration and council pressed a narrative that fire and police overtime, and other unspecified inefficiencies, are systematically eating up the city budget.

CM Fife: “[Director Roseman, you said] that primarily the expenditures that are pushing us into the structural deficit are our public safety services and police and fire. And that as I read in the report, that if we did not address those two departments and relied on all other departments in the city of Oakland, it would constitute approximately 83% in cuts to all other departments if we left police and fire as is.

Director Roseman: “Yes”

CM Fife: “So is there a plan?”

The assumption underlying these statements is that police are wildly inefficient. The city and council plainly laid out this rationale when they commissioned a staffing study in October of 2023 to examine the issue.2 In a memo requesting waiver of competitive bidding for the study, city Inspector General, Michelle Phillips notes:

“The City Council, Mayor, and members of the Oakland community have questioned the effectiveness and efficiency of OPD’s use of staffing resources … The examination of OPD staffing, alternative responses to calls for service, and possible civilization of some OPD functions is critical to effective, efficient, and sustainable police reforms in the City of Oakland. This information will be helpful to the Chief of Police (when selected) to ensure current resources are managed appropriately and in a fiscally responsible manner.”

The refrain of “police caused our deficit” is repeated laconically by the media. And it’s harnessed by the labor unions (namely SEIU, IFPTE Local 21 and IBEW Local 1245, and IAFF Local 55) to attack the police.

But this singular focus on public safety as the root cause of all budget problems is willful misinformation. It’s a negotiating tactic to influence public sentiment in favor of protecting spending on city administrative jobs, social services and “police alternatives”—the more politically palatable incarnation of “defund the police.”

The strategy has worked for years. It has diverted the public’s attention from the full spectrum of fiscal issues, and provided the city and council with political cover to steadily shift funds away from public safety. Spending on administration and social services has ballooned by 62% over the past 5 years. Most of those departments even received increases in the latest budget cycle, while police and fire departments were cut aggressively.

The misinformation canon

The political capital to maintain this attack on public safety flows from a core set of oft-repeated myths:

Myth 1: Any cuts to non-safety department budgets would decimate them

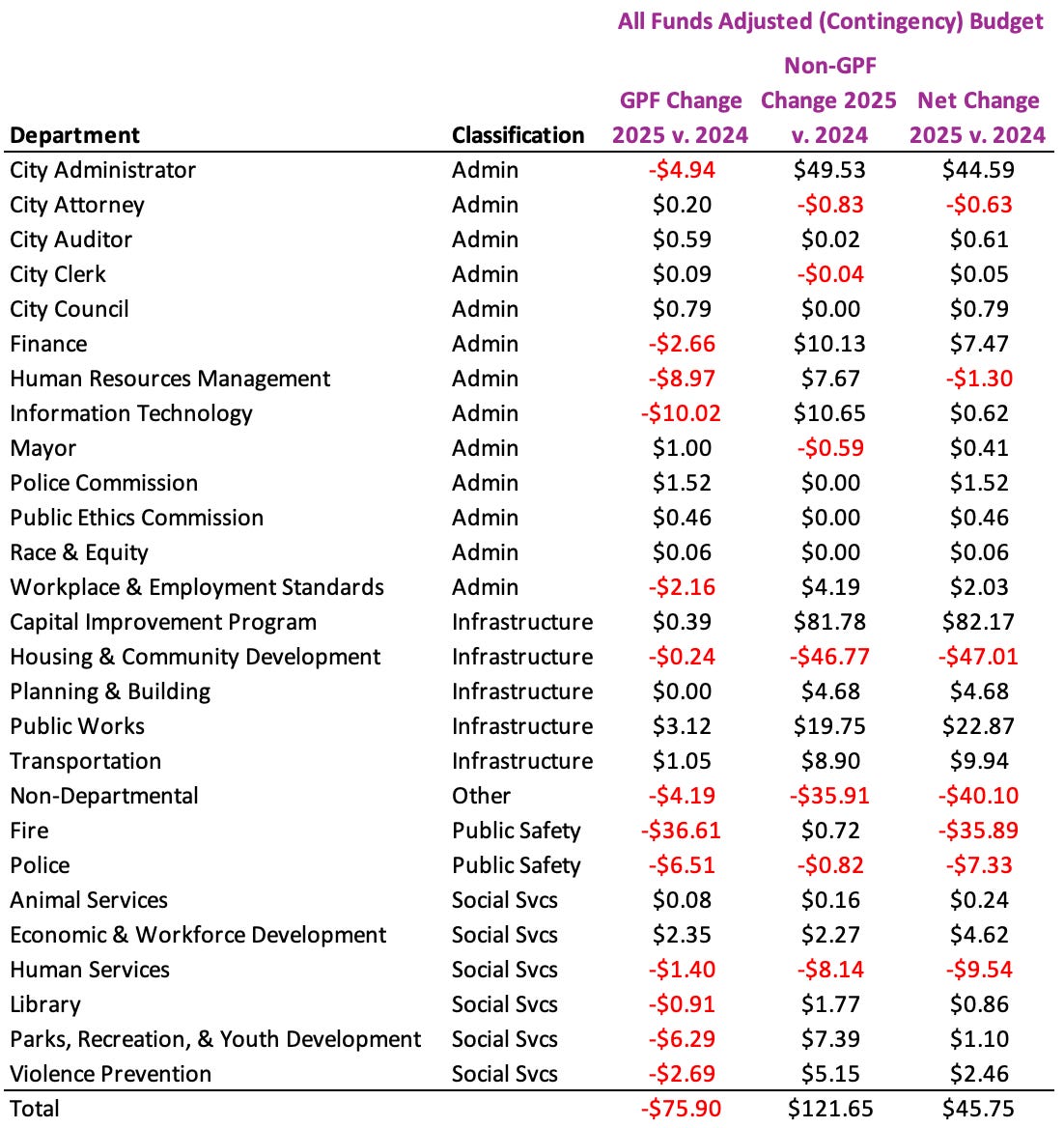

Reality: The city’s Q1 revenue and expense report, describes only a portion of departmental budgets—the part funded by the General Purpose Fund (GPF). It does not report their overall budget (a.k.a. their “All Funds” budget). The GPF comprises one third of city spending, the non-GPF funds comprise the rest.

Non-safety departments are primarily funded out of the larger non-GPF sources. This substantially reduces the negative impact of any cuts to their GPF budgets. If non-safety departments lost 50% of their GPF budget, many departments would keep most of their overall budgets intact. For example, HR would retain 99% of their budget, IT would keep 93%, Transportation would keep 89%, and Violence Prevention would keep 85%.

On the contrary, police and fire departments are funded almost entirely with GPF monies. When cuts are made to their GPF funds, their overall budgets are slashed almost proportionally. If the city cut the GPF budget by 50%, police would retain only 54% of its overall budget. Police have little other funding to buffer the impact.

Despite this disproportionate impact of GPF budget cuts on public safety, the city council doggedly protects non-safety departments. And they justify this position using deceptively incomplete budget information to claim that non-safety departments would be decimated unless police and fire are slashed.

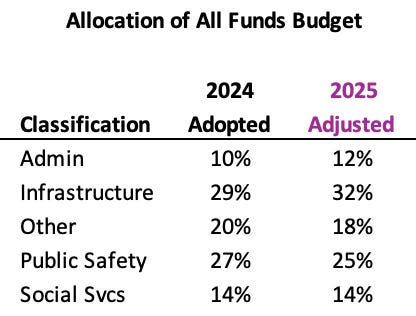

Myth 2: Police and fire are more than 60% of the budget3

Reality: Public safety (police + fire) represents 25% of the current city All Funds budget. The rest of the budget is allocated to administration (10%), social services (16%), infrastructure (32%), and other non-departmental (18%) spending.

When city and union leaders claim public safety is the vast majority of “the budget,” they are talking only about its share of the GPF budget. But that share is about 65% of one third of the budget—i.e., 22.5% of the overall budget. (The remaining 2.5% of their overall budget comes from non-GPF sources.)

Rather than acknowledge this reality, city and union leaders exploit an incomplete view of the budget to confuse the public and justify disproportionate cuts to public safety spending.

This attack on public safety spending has succeeded. Over the past five years, the budget for public safety spending has fallen by 11% in real dollars—and that’s before the city’s October 1 contingency budget cut it 16% further—while administrative and social services spending rose 31% in real dollars.

In terms of personnel, fire and police staff has shrunk by 18% since 2020 (including contingency cuts), while administrative staff has grown 3% and social services staffing increased by 13% (including contingency budget changes).

Myth 3: Non-safety departments have already made significant cuts

Reality: 19 of 25 departments were given budget increases in the contingency budget effected on October 1. The increases ranged from 1% to 44% over the prior fiscal year.

Only six departments had budget cuts. They are Human Resources (-$1.3M, -6%), City Attorney (-$0.6M, -2%), Human Services (-$9.5M, -6%), Fire ($-35.9M, -16%), Police (-$7.3M, -2%), and Housing & Community Development (-$47M, -29%).

Once again, the deception revolves around GPF vs. overall budgets. When the city reduced its GPF allocations to non-safety departments this year, it compensated by increasing non-GPF fund allocations to those same departments, thereby avoiding overall cuts and even increasing budgets for most.

To do this, the city council suspended voter-mandated restrictions on non-GPF spending in the July 2 budget resolution; they declared an “extreme fiscal necessity” and authorized use of restricted funds for unrestricted purposes. That allowed the city to drop police staffing to 600, below the 678 mandated by voters when they passed Measure Z, and below the 700 mandated by the newly passed Measure NN.

On the other hand, the city cut fire and safety GPF budgets without compensatory increases in funding from non-GPF sources.

Bottom line: cuts have been disproportionately focused on public safety even though non-safety department budgets have room to accommodate budget cuts without decimating all their services. Such cuts to public safety are a policy choice, not a fiscal necessity, and they are enabled by presenting an incomplete view of departmental spending.

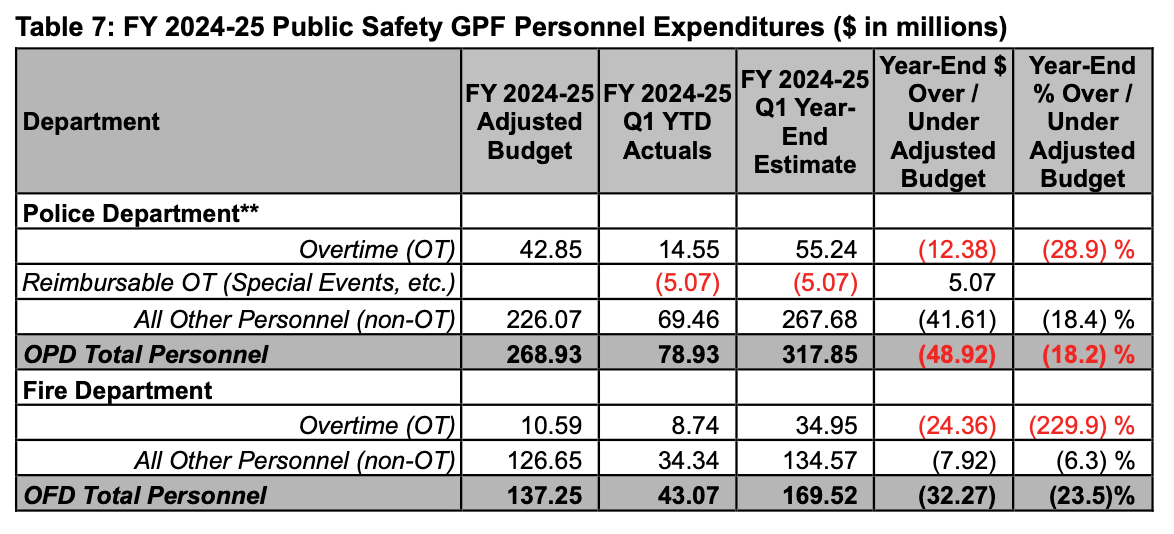

Myth 4: The deficit is all due to fire and police overtime

Reality: Police overtime is projected to be $7M over their $43M overtime budget. While not insignificant (that’s 2% of their 2025 contingency budget), it is not the $52M implied by council and media discourse. Moreover, this is less than the overtime spending overruns typical of the past five years.

The fire department is projected to be $24M over budget on overtime, which is on par with overruns of the past 5 years.

But even if both departments were spending on-budget, the budgeted overtime is large: 12% of the police budget and 6% of the fire department budget. It begs the question: why are those overtime budgets so large in the first place?

It is the unavoidable consequence of the city council understaffing police in search of police alternatives, an HR department that has failed to staff open positions, and oversight bodies that layer on additional police reporting and internal investigation tasks.

Former Chief LeRonne Armstrong explained to Oakland Report many of the additional burdens that consume officers’ time and reduce police efficiency, while driving up overtime hours. These include:

Each stop made by an officer involves 10 minutes to resolve the actual offense and 20 minutes for paperwork.

Every response to a call for service requires the officer to fill out a report.

Officers must upload and manually annotate the footage from their body cameras.

Officers are disciplined if they do not file reports in the same day.

Due to the Negotiated Settlement Agreement requirements, all levels of Use of Force (down to the least severe Level 4 incidents) now require a report and approval. Each takes hours to complete. Prior to the NSA, reporting detail was scaled to the severity of the incident.

Police could do their reports in the car, or they can wait til the end of the shift. The former means police are not patrolling the neighborhood, the later means overtime.

The city has not invested in technologies to simplify and automate these reporting activities.

Others in OPD leadership identified additional issues that drive increased time demands on police. These include:

Closure of the Glenn Dyer jail in downtown Oakland in 2019, which demands that officers now spend 1.5 hours driving arrested suspects to Santa Rita jail in Dublin.

Elevated crime levels and resulting arrests mean more time in mandatory court appearances, which takes officers off patrol or drives overtime.

Violent crime scenes demand additional officers to secure the area and support investigation work.

In addition, the city council and administration constantly demand more from police and fire services, both through formal programs like Ceasefire and sideshow suppression, and through backchannel requests from council members for extra patrols in their districts.

Multiple high-ranking city officials told Oakland Report that council members frequently make unofficial requests to police area captains to increase patrols in their neighborhood. The frequency of such requests increases when council members are under constituent pressure or up for re-election. Though council members are prohibited from directing staff, or even communicating with administration staff without direct oversight by the city administrator, conversations take place anyway. Such conversations typically involve an inquiry like: “what are you doing to address the elevated crime in my district?” And the response from the area captain is: “We’ll increase crime suppression special operations.”

It’s not wrong for city leaders to ask for high levels of police and fire services—they are essential to a city’s health and economic development. But it is manipulative and unethical to undermine and blame public safety for cost overruns, while effecting policies and managerial actions that drive those very overruns.

There is related speculation circulating in the media that overtime spending is the result of abuse of “comp time.” This is based on a 2019 city auditor’s report which called out the potential issue. Comp time is when an employee is given 1.5 hours of extra time off for every overtime hour worked (instead of extra pay). When that time-off is used, it forces another officer to cover the shifts with their overtime, leading to payment of 1.5 x 1.5 = 2.25 hours of costs paid out to the second officer.

According to the Oakland Police Officers Association, time-off requests are limited to 3 officers per patrol shift, thereby limiting the potential for this cascading cost.

Nevertheless, there is presently no data on whether this issue is a significant driver of overtime costs, and would be worth inspection and resolution. Until then, claims of abuse are just political talking points. A formal review will resolve the reality, and also help quantify the impact of understaffing on the need for overtime hours. If done properly, and without bias or interference by city leaders, the overdue study of police staffing needs should shed light on this.

Myth 5: The deficit is due to unchecked overspending by fire and police.

Reality: City council adopted a budget on July 2, 2024 that increased police funding by 6% and cut fire by 8% The fire and police departments are projected to overspend this by $17.3M and $23.6M respectively.

Then on October 1, 2024 the police and fire budgets were cut an additional $17.2M and $28.3M respectively, thus exploding the projected deficit to $34.4M and $51.9M overnight (see spreadsheet for budget details).

Half of the $85M of the overspending by police and fire is due to this real-time reduction in their budgets on October 1st. The other half of overspending is due to the city maintaining or even increasing demands on fire and police services, and increasing employee compensation, while reducing their budgets.

It is a kind of manufactured deficit, a self-justifying decimation of departments. By cutting the budget in real-time and then placing additional service burdens on the departments, the cost overruns immediately explode. Those overruns are then used to claim waste and abuse, and thereby justify further cuts to the same departments.

This is analogous to the city dropping the speed limit by 15 mph while a person is driving down a road, and then handing him or her a speeding ticket. The person wouldn’t have had a chance to react and adjust. And when they don’t pay the ticket on time, they get fined more and thrown in jail.

Why are these myths promoted?

In short, these myths fulfill both ideological obligations to progressive doctrine, and support the transactional politics of narrow interests that help get city leaders elected.

The myths are convenient for council members because they would (if true) imply council members are not culpable for their policies and actions that drive overspending. The myths are also a convenient for labor unions who are attempting to capture political ground in advance of the inevitable negotiations for wage and benefit concessions.

Lost in these transactional politics is a key data point—only 32% of city full time employees are residents of Oakland.4 While there is nothing unreasonable in employing the best workers from anywhere in the region, it sets up a perverse incentive to abuse Oaklanders’ interests. Those workers and their union leaders can maximally extract Oakland resources for their benefit, but personally avoid the negative impacts associated with the decline of city services.

So what can be done?

First and foremost, the city and the council need to stop raiding public safety resources and redistributing them to administrative and social service activities. And in their budgeting decisions, they need to weigh the full budgets of each department, not just the GPF portion. They need to apportion resources according to the reality of Oakland’s streets—excessive crime, urban blight, rampant dumping, and severe homelessness—not ideological doctrine, transactional politics, or wishful thinking.

The city needs to face the realities of our budget problems, and not give in to lobbying by narrow interests. The city has a serious problem with unsustainable compensation increases. That must be corrected.

And yes, police efficiency is low and it needs course correction. But to fix it, the city and council needs to stop pointing fingers and look in the mirror. Police inefficiency is the direct consequence of counterproductive policies enacted by the city, the council, the police commission, and unaccountable federal oversight.

On top of this, the council and city leadership constantly attack police and then demand more services that require more overtime. This destroys morale. And low morale destroys efficiency and effectiveness of an organization.

Yes, the city is in a bind. The council didn’t do what it should have done when it should have done it. And now we’re all going to have to pay the price, public safety included.

But that doesn’t mean the city should disingenuously shelter all non-safety departments by sacrificing its most essential one—public safety. Public safety is the very foundation of a civil society and a growing economy.

Oakland’s leaders and a pliant media are deliberately aiming to further cut the 25% currently spent on public safety, while leaving other spending virtually untouched. That’s a choice that may amplify the city’s safety crisis and exacerbate its downward economic spiral.

High level city sources suggested to Oakland Report that Nikki Bas directed the city administrator to remove the original FY2024-2025 Q1 Revenue and Expense report and replace it with a redacted one that deletes the statement “failure to take dramatic and immediate steps to reduce expenditures will almost certainly result in insolvency” and removes discussion of potential bankruptcy.

This raises the question of whether Bas has been violating the city charter by directing administration budgetary policy and recommendations. It’s a question that Oakland Report has pursued, but CM Bas and the city administration has stonewalled it by refusing to comply with our public records request detailing her communications with the city regarding the budget.

The report was supposed to be completed in July and delivered in final form no later than December. It hasn’t been delivered, and there is no sign yet of it coming in the forthcoming council agendas.

This myth has been circulating since at least 2016. It was addressed by Oaklandside in 2021, but the myth persists.

Amazing work

Excellent article, Tim. Thank you for the insight!