Oakland’s MACRO is 5 times more expensive than the police services it displaces

And its benefits to quality of life remain unknown

In 2021, Oakland’s City Council launched Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACRO) as a transformative alternative to policing that could save the city millions of dollars, improve racial equity in public safety, and improve quality of life. Two years later, we used the City’s data to assess that promise. Our in-depth analysis reveals that MACRO saves 17 cents in police costs for every dollar it spends. We also find that MACRO’s impacts on racial equity and quality of life are largely unknown due to lack of rigor in problem analysis and impact assessment by the City. Although MACRO is not presently meeting any of its mandated goals, we identify several reforms that could help it deliver greater benefit to Oakland in the future.

At the September 26, 2023 Oakland Public Safety Committee meeting, MACRO Program Manager Elliott Jones reported that the majority of MACRO’s service volume was now coming from Oakland Police Department (OPD) dispatch.1 Over the prior year, it increased from 2% to 58% of MACRO service contacts. MACRO, it seemed, was starting to deliver on its promise to unburden OPD of non-violent, non-emergency calls.

But Mr. Jones didn’t say anything about the most obvious questions: what portion of police burden was MACRO relieving, and what were the police cost savings achieved?

In fact, throughout the life of MACRO, from conceptualization to the most recent impact report, the City has reported no information on the OPD load reduction, nor the associated cost savings, nor any cost-benefit assessment of its impact on client or community quality of life.

So we did that research and analysis.

MACRO was initially funded in 2020 by the Oakland City Council as part of the effort led by Council President Rebecca Kaplan and Council Member Nikki Fortunato Bas to cut the police budget by 50%,2 while delivering more equitable outcomes to BIPOC communities (“Black, Indigenous, and People of Color”)3 who are “most impacted by the lack of housing, economic stability, support services, over-policing, inter-communal violence and the carceral state.”4 Modeled after the CAHOOTS program in Eugene, Oregon, MACRO seeks to reduce police costs, reduce interactions between BIPOC individuals with police, and facilitate access to social and health services for BIPOC individuals.

In practice, MACRO has functioned primarily to serve Oakland’s homeless population, with a particular focus on those in drug or mental health crisis. 92% of MACROs service recipients are homeless.

But people are free to refuse MACRO’s support, and generally they do refuse. Residents only accept help in 19% of cases. And fewer than 6% of MACRO cases result in the provision of mental health or drug treatment services.

Moreover, MACRO’s employees are not equipped, trained or permitted to handle most of the mental health issues that arise in the community. Thus, they must call or defer to Alameda County Behavioral Health or the Oakland Police Department to address such situations.

“Rick [MACRO responder] pleads with [the homeless man] to go to the hospital, but the man says no, not today. And so, after 15 minutes, we leave. When we get in the car, Rick seems frustrated. What do you do when the person you’re trying to help doesn’t want to be helped?”5

MACRO is also expensive. Each of its referrals costs MACRO nearly $3,000. Overall, it spent $3.1M in 2023 to deliver its services and has a $9M budget for 2024 to triple its staff.

Meanwhile, MACRO saves the Oakland Police Department very little. Based on its current service volume, it is saving police only $532K per year. That’s 17 cents saved for every dollar MACRO spends. Even with its planned expansion, and a large increase in operational efficiency, MACRO would save only 20 cents in police costs per dollar spent.

Despite the fanfare and good intentions surrounding the launch of MACRO, it has not proven to be a cost-effective alternative to policing in Oakland.

To be fair, there are other potential benefits of MACRO besides cost savings. These might include better or faster resolution of community disturbances caused by homeless persons (e.g., at libraries and schools). Or MACRO might improve the quality of life for homeless persons whom they do help to access available social services.

But MACRO provides little or no data to quantify such benefits and no assessment of its impact on clients or community. Therefore, it is impossible to conclude that MACRO is succeeding against any of its mandated objectives; and it is difficult to justify spending the forecasted $9M/year on MACRO when the City faces a growing budget deficit and many competing priorities.

In the remainder of this article, we dive into the history and motivations for MACRO, and the data supporting our findings. We end with some suggestions on how MACRO might be reformed to deliver more value to the community, including stepping back to perform a rigorous problem analysis before putting more resources into the current operations.

1 – Why was MACRO created and why does it focus on the homeless?

MACRO emerged from Oakland’s City Council in July 2020 as a flagship initiative to reduce police spending in Oakland by 50%.6 This defund effort was catalyzed in the wake of George Floyd’s death and sought alternatives to traditional policing.

In addition to seeding a MACRO pilot, the Council created the Reimagining Public Safety Taskforce (RPSTF) to recommend additional options to achieve the defunding objectives.7 The RPSTF final report, issued in April 2021, offered dozens of recommendations, including MACRO expansion.8 This expansion was then prioritized by Council Member Carroll Fife and Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas in May 2021 via Council Resolution 88607.9

It is also worth noting that a subgroup of the task force implored the RPSTF steering committee and Oakland leaders to proceed carefully and cautiously with changes, and consider that “lives will be lost if police are removed without an alternative response being put in place that is guaranteed to work as good as or better than the current system.”10 This subgroup emphasized that improved safety and crime prevention is of great concern to Black communities of Oakland, “who are disproportionately experiencing and bearing the brunt of crime and violence.”

But with the memory of George Floyd still fresh, and the historical reality of policing and incarceration in Oakland, the prevailing view of policing was negative. This milieu fueled the political drive to establish MACRO urgently.

The basic structure of MACRO was specified in September 2020 in a report by the Urban Strategies Council (USC) which was commissioned by the Council to assess the feasibility and design of MACRO.11 USC based its recommendations on the CAHOOTS program, which is composed of civilian responders to non-violent, non-emergency incidents in the community.

Following the USC report, MACRO was vigorously promoted by advocates as “transformative alternative response to police”12 that would save millions of dollars in police expenses,13 and would improve equity and quality of life outcomes for BIPOC and people in mental health and drug crisis.14 The USC report stated that these individuals were at the highest risk of trauma and harm by police interactions,15 and MACRO, advocates suggested, would reduce the interactions between such populations and police. In a March 2021 City Council Motion, Council Member Rebecca Kaplan noted:16

“Groups in Oakland like the Coalition for Police Accountability and Anti Police-Terror Project have long pushed for eliminating a police response from circumstances where other methods could be more humane and effective.”

But the desire to address potential police harms to BIPOC communities does not directly explain MACRO’s present focus on homeless communities. We found the rationale in various City Council discussions and documents concerning MACRO’s formation. There it was emphasized that the majority of homeless are BIPOC and that homeless persons suffer from high rates of mental illness and drug use.17 Thus, the Council and its advisors believed the homeless population should be prioritized in MACRO operations because they contain a high concentration of persons with the targeted demographics.

MACRO was also touted as a union-job creation program. As noted by Felipe Cuevas, SEIU 1021, City of Oakland Chapter President:18

“These positions must be the kinds of good, permanent, in-house, union jobs that allow working people to get ahead in Oakland and that lift up our whole community.”

In addition, these jobs were seen as an economic rehabilitation opportunity for those harmed by crime or impacted by past police interactions. The RPSTF noted that MACRO should prioritize “recruiting and hiring impacted BIPOC residents to serve their communities as MACRO responders and EMTs.”19 In turn, the City Council prioritized the training of such community members for MACRO roles in its March 16, 2021 Resolution directing the formation of MACRO:20

“WHEREAS, training of the MACRO team is essential to its effectiveness, and such training should advance the goal of MACRO to create a transformative alternative response to police, where community members that have been at the center of violence (as victims or perpetrators) are considered for hire as responders.”

Thus, MACRO was enthusiastically created by the City Council with the hope it would address racial equity in public safety, mental health issues and social services for the homeless, jobs for marginalized populations, and quality of life issues for the community—all the while reducing public safety costs.

In the closing of her March 2021 Motion, Council Member Kaplan noted confidently that “the MACRO model is no longer experimental” having been launched in other cities. “The question is no longer whether MACRO could work, but how to make it work best for the City of Oakland,” remarked Kaplan.

And so, after another year of preparations, the Oakland Fire Department launched MACRO on April 9, 2022 as an 18-month, $15M pilot program which aimed to expand to 57 staff members.21 Of those staff, 42 would be responders working 24/7 shifts in two-person teams. That program was supported by a $10M State of California grant, and the pilot was completed on October 9, 2023.22 Ongoing funding for MACRO has yet to be determined, but the program continues to operate and expand staff.

The five goals of MACRO, as mandated in Council Resolution 88576,23 are a combination of racial equity and police cost-savings:

Decreased negative outcomes from law enforcement response to nonviolent 911 emergency calls, especially among Black, Indigenous, People of Color;

Decreased criminal justice system involvement for people in crisis, especially Black, Indigenous, People of Color;

Increased connections to community-based services for people in crisis, especially among Black, Indigenous, People of Color;

Redirection of MACRO-identified 911 calls to an alternative community response system; and

Reduced Oakland Police expenses and call volume related to 911 nonviolent calls involving people with mental health, substance use, and unsheltered individuals.

2 – Unresolved questions

Amidst of the optimism and advocacy for MACRO, a key recommendation of the RPSTF was either ignored or overlooked: “the City should also calculate annual cost savings from continued reductions in 911 calls responded to by OPD.”24 And even now, after completion of the MACRO pilot, the City or MACRO still has not provided any such calculation, nor whether those savings warrant the $9M per year budgeted by the City to operate MACRO.25

MACRO also has not quantified whether it has delivered a significant reduction in negative interactions between its clients and the police, or if it has substantially improved the quality of life of those clients or the community. To date, MACRO has only tracked the quantity of contacts and referrals it has made, not its outcomes and impacts.

We also note that MACRO’s service to the unhoused community, even though noble, does not necessarily address the needs of a much larger population of Oakland housed residents who may be negatively impacted by crime and the criminal justice system. It remains an open question whether it was the right decision for MACRO to focus on homeless populations. Namely:

Are we benefiting Oakland residents who are most impacted by crime and criminal justice when we prioritize service to homeless persons?

Do not low and middle-income housed residents of Oakland have even more compelling needs with regard to crime and criminal justice?

These questions are made all the more poignant given the hundreds of millions of dollars already spent by the City, County and State to address homeless and behavioral health needs, including multiple mobile crisis services to serve such populations.26

3 – What services does MACRO provide?

MACRO is designed and permitted only to handle non-violent, non-emergency needs of the community that do not involve law enforcement issues. MACRO primarily focuses on issues related to homelessness, mental health, and drug/alcohol use, for reasons noted above.

In a recent series of articles, journalist Wren Farrell of KATW illustrates a ‘day in the life’ of MACRO after joining them for a series of ride-alongs.27 Noticeable in these stories is the intense effort by MACRO responders to convince homeless persons to accept social and health services, but these individuals often refuse. In fact, they refuse more than 70% of the time, and MACRO departs with no further action. This outcome is inherent to the design of MACRO.

The Urban Strategies Council emphasized that the success of the MACRO model depends on the referral of its clients to community-based and government care services, and those hand-offs require direct transport by MACRO staff with warm hand-offs to care providers, and follow-up support.

"Under the MACRO model, whenever possible, a team of Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs) and counselors will respond to and provide medical assessment/clearance, de-escalation and support, and connection to care. Connections to care can be immediate...Transportation and follow up would be voluntary...The MACRO team will also provide follow-up support to connect to additional available resources including clinical care, medication access, and residential treatment or drop-in clinics."

But acceptance of such services must be voluntary. MACRO and the Oakland Fire Department, where the MACRO program is housed, are not permitted nor trained to transport patients (who may need involuntary, emergency, or advanced medical care). Only police, paramedics, or certified mental health clinicians have the authority to commit an individual involuntarily to services or treatment.

Also, for both employee safety and to comply with the City’s labor union agreements, the Oakland Fire Department and City employees are not permitted to respond to 5150 situations28 (where a mental health patient presents a danger to themselves or the community and may be detained against their will), nor to situations of real or perceived violence and risk of harm.29

In 2022, 68% of OPD’s Community Caretaking stops, which includes mental health calls, were 5150 actions (1,441 out of 2109 stops). The high proportion of 5150 outcomes for these stops reflects that 99.9% of mental health dispatch calls were Priority 1 or 2 (urgent), and none were MACRO eligible (data provided in the Appendix). MACRO employees simply are not equipped or trained to deal with such situations.30

Even if MACRO did have authority and training to enforce involuntary services or treatment, it is contrary to policy and principles of the program, where building trust with the community is prioritized over other outcomes.31

4 – How does MACRO operate?

MACRO services are initiated from three sources: (1) calls dispatched from 911 to the MACRO team, (2) direct community calls for service via email (and via a direct phone number starting in Q1 2024), and (3) “on-view” calls, which are self-initiated interactions by MACRO units. A MACRO unit is composed of a pair of responders: a Community Intervention Specialist (CIS) and an Emergency Medical Technician (EMT).

When a MACRO unit responds to a call, they assess the situation to assure safety, then confer with the service recipient to assess their needs. If needs are within the training and protocols of the CIS or EMT, they may be addressed directly with recipient permission. Alternatively, the MACRO unit may transport the recipient to a referred entity or call the entity to assist. If the recipient refuses services, MACRO provides them with water and, if needed, a blanket. All interventions are voluntary by the recipient.

MACRO currently tracks various data about each contact, including the race and identity of the recipient to assess equity objectives. On average, MACRO services 434 contacts per month (5208 contacts per year) based on Q3 2023 data32; 92% of contacts are with homeless persons, 66% are with Black residents, and 83% with BIPOC individuals.33

Given the objectives of MACRO to reduce police load and address mental-health issues, we note these key statistics from Q3 2023 which reflect MACRO’s current operating state:

138 contacts per month (31%) are transferred from 911 Dispatch (1,656 per year);

85 contacts per month (19%) are mental health related (1,020 per year);

84 contacts per month (19%) are resolved by referral to public or private social services;

Overall, 26 contacts per month (6%) resolve with the provision of health, mental health, or drug treatment services (312 per year).

The figure below shows the flow of call handling from initiation. Counts reflect the average monthly service volume during the most recent quarter of MACRO operations (Q3 2023).

5 – Does MACRO reduce police costs?

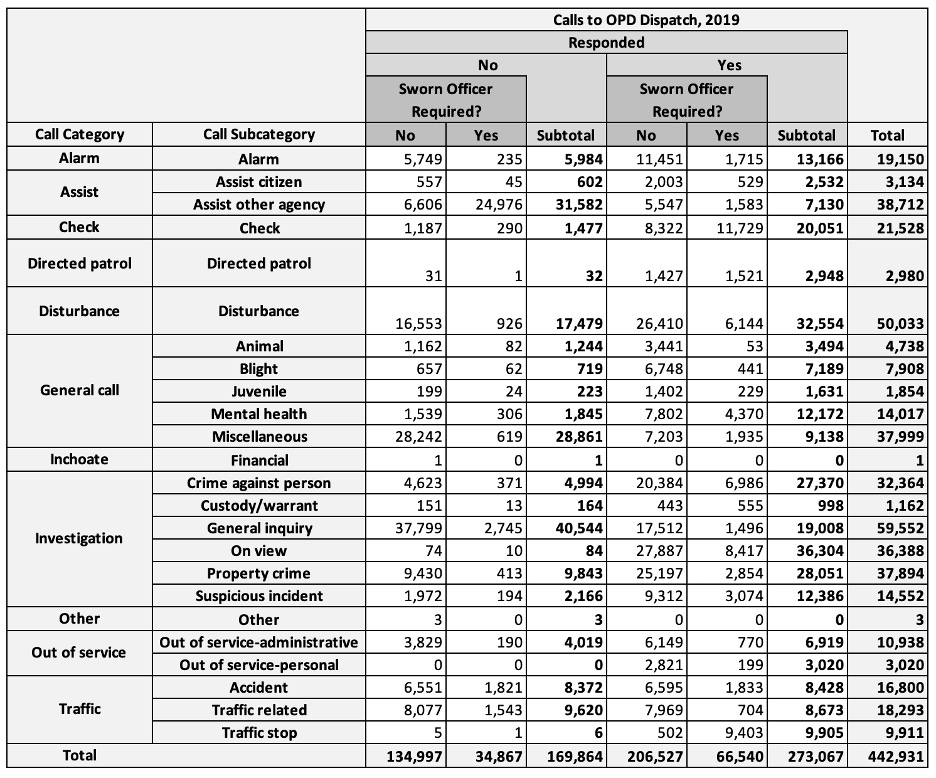

To estimate police costs savings by diversion of calls to MACRO, we obtained log data for all calls to Oakland 911 in 201934 and labeled the call categories according the the report provided to the RPSTF by the Center for Public Safety Management.35 This data already categorizes calls based on whether a sworn officer is required. We further categorized all calls as MACRO-eligible using the list of MACRO-accepted call types.36

For this analysis, we do not distinguish police and fire dispatched calls; we treat all dispatches as police dispatches because only 5% of 911 transfers to MACRO are from Fire Dispatch. Thus, even if the costs of firefighter response are different than the costs of Police response, the impact will be only a few percent error in our estimates.

In total, 442,931 calls were handled by OPD dispatch in 2019, of which 341,524 did not require the presence of a sworn officer (77% of calls). Of those calls, 10,997 were MACRO-eligible and 5,732 (52% of eligible calls) were serviced by the police. The others did not receive a police response, presumably due to insufficient police resources.

Table 1: Tabulation of calls to OPD Dispatch calls in 2019. Highlighted cells are MACRO-eligible. Calls are divided into MACRO-eligible and MACRO-ineligible based on the supported call types published by MACRO.

These 5,732 calls represent 1.29% of OPD Dispatch calls that received a police response in 2019. And they required 1.41% of total annual police effort based on time data provided with the call logs. Thus, the maximum load that MACRO could unburden from police, given current MACRO service policies, is 1.41%.

Note that the CAHOOTS program (upon which MACRO was based) diverts 3-8% of police calls,37 suggesting MACRO’s service criteria may currently be too narrow. We return to this point in our recommendations below.

The average fully-burdened cost of a sworn OPD officer is $272K and there are 456 sworn patrol officers budgeted at OPD.38 There is also about a 5% overhead for administrative staff to support those patrol officers. Therefore:

A 1.41% reduction in OPD service load amounts to $1,836K in maximum potential cost savings for police (1.41% * $272K * 456 * 1.05 = $1,836K).

MACRO is currently staffed with 19 responders and 2 managers39 who handle 1656 calls from 911 per year (138 per month). Assuming OPD receives the same number of MACO-eligible calls in 2023 as in 2019,40 then MACRO is currently diverting 29% of eligible calls from OPD (1656/5732 = 29%). Therefore:

MACRO is presently saving $532K of OPD costs per year (29% * $1,836K = $532K).

MACRO’s costs this year for salaries, operating expenses (computers, software, materials and supplies, fees, etc.) were $3.1M.41 Therefore:

MACRO saves 17 cents of police costs for every dollar spent ($532K/$3,100K = $0.17), a negative 83% return on investment annually.

One might argue that direct calls to MACRO from the community should be included as police diversions and added to the cost savings. To account for this possibility, we also estimate the best-case savings scenario within the current operating plan. That plan expands MACRO to a staff of 57,42 including an increase from 19 to 42 responders, with a budgeted cost of $9M/year. This would allow MACRO to handle 64% of MACRO-eligible OPD calls (based on proportional scaling of current service volumes). We further assume that MACRO efficiencies will significantly improve by displacing many of its on-view calls with 911-dispatch calls, and that direct community calls also displace police dispatch. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the fully staffed MACRO team will handle 100% of the 5,732 MACRO-eligible calls. Therefore:

In the best-case scenario, MACRO would save $1,836K of OPD costs per year—a savings of 20 cents in police costs for every dollar spent ($1,836K/$9,000K = $0.20).

It’s important to note that these estimates are potential savings, not necessarily actual savings. A deeper analysis of police operations management would be required to understand if the observed load reduction by MACRO allows patrol officers to pursue other more productive work duties. We hope that it would, but other operational constraints may prevent such redirection until police call load is reduced to a sufficient level.

6 – Does MACRO meet its equity goals?

Many of MACRO’s goals are equity oriented: to reduce police interactions with people in crisis, particularly those with mental health issues and BIPOC persons, and to improve quality of life and health outcomes for those populations.

But over the last 3 months of the MACRO pilot, 59% of MACRO’s calls end with services refused by its clients, and MACRO is unable to locate the client in another 18% of calls. In other words, for 8,174 of its 10,616 calls last year, MACRO did no more than would have been done if MACRO did not exist. While 19% of contacts accepted referrals, the outcomes of such referrals have not been reported, so it is unclear if these referrals resulted in significant benefit to the clients.

MACRO argues that the value of its interactions with the community is trust building, even when service is refused.43 This implies that service acceptance rates will increase with time. But over the 18-month pilot the acceptance rate remained largely steady—with both the first month and last month of the pilot reporting a 22% acceptance rate for referrals.44 So there is, as-yet, no evidence the trust-building is working.

While these points are suggestive of limited impact, they are circumstantial at best. They do not specifically assess the effect of MACRO on its equity goals. Unfortunately, such a definitive assessment is not possible given the lack of data from MACRO or the City.

When forming MACRO, the City did not provide any quantitative data on the negative impacts of police interactions with the community served by MACRO. It offered only narrative perspectives from advocacy groups. Nor did MACRO assess client and community outcomes during its pilot. Thus, we have neither the pre-MACRO baseline data nor the post-MACRO outcomes data to assess if diversion of police contacts has a positive impact on resident quality of life.

Nevertheless, MACRO might deliver quality of life benefits in other ways. For example, if MACRO efforts were leading to permanent resolution of homelessness or health issues for clients, then it might lead to a gradual reduction in the population needs over forthcoming years. But we cannot assess this possibility. MACRO does not provide (or does not collect) case data on whether its clients transition out of homelessness or improve their health issues.

In fact, MACRO reports that 45% of recipients are repeat clients,45 indicating that many clients are not seeing improvements. But reliable conclusions cannot be made at this time without more detailed case data from MACRO.

Furthermore, we don’t know the rates of client exit from these issues without MACRO services, making it unclear what additional benefit MACRO is delivering over and above the services that already existed in Alameda County before MACRO was formed.46

Moreover, the City and the Urban Strategies Council did not perform problem analysis of pre-MACRO social and health care services that were and continue to be offered to homeless persons. Thus, it is not clear where such pre-existing programs were succeeding, if and where they were falling short, and how MACRO would close those gaps.

In summary, to properly assess the impact of MACRO on client and community outcomes, MACRO needs to carefully gather (1) case data on the health and life outcomes individuals it serves, (2) data on the health and life outcomes of individuals who do not use MACRO services, and (3) data on the relative impact of MACRO services compared to many other entities in Alameda County that provided social services and health care prior to MACRO.

7 – Bottom line: MACRO is not meeting its goals

In its current configuration, MACRO has negligible benefit on police costs, has had only limited success in getting its clients help through referrals, has no indication that it has reduced negative interactions between its clients and police, and provides no data on whether its clients achieve improved life outcomes.

Only 19% of MACRO’s calls result in a successful referral to social or health services in Alameda County. At current service rates, that represents 1,008 referrals per year at an average cost of $2,976 per referral.

That’s a lot of money to refer or transport an individual to a social service provider, particularly when such providers already offer community outreach and mobile response units that may have been able to reach these individuals without MACRO intervening.

Taken together, our findings suggest MACRO is not meeting any of the five goals mandated by its founding City Council Resolution.

Moreover, because MACRO was launched without a rigorous and quantitative problem analysis of unmet needs of BIPOC communities and people in crisis, it’s not clear if MACRO can offer additional quality of life benefits beyond that already offered by pre-existing Alameda County, City of Oakland, and private social services.

Before residents of the City of Oakland are asked to continue its funding at $9M/year, several fundamental questions that deserve to be rigorously answered by the City Administration and City Council. Anything less will just propagate inefficient use of significant City resources that could have much greater impact elsewhere.

What are the gaps in the pre-existing network of existing County, City and private social, health, and safety services? Which of those are MACRO addressing? Is MACRO complementary or redundant?

What is the benefit to quality of life for persons served by MACRO? This must include a quantitative assessment of the suggested harms by police, whether MACRO has reduced them, and whether MACRO interventions have improved health or life outcomes.

Should homeless populations be the priority service recipients for MACRO? Would a different mandate better serve the needs of BIPOC residents in general, including housed residents, and people in crisis?

Can it be reconfigured to deliver the same services at a much lower cost?

The City must also address an even more fundamental question: was MACRO set-up to fail? MACRO is constrained on who it is allowed to serve (mainly people in crisis and not the broader community), limited in what it can do for those people (offer voluntary referrals to care services), and largely reacts to unaddressed root causes of the homelessness and mental illness problems. Given all that is working against it, MACRO seems to serve as little more than a street-side palliative support agency for individuals in crisis.

8 – Could MACRO be fixed?

Despite its numerous struggles, there is one bright spot in the data on MACRO so far: its services have helped address disturbances by homeless people at public institutions such as the library and schools.47 OPD generally does not have the resources to dispatch officers to address such situations, and thus they go unresolved or are left to employees of those institutions to handle themselves.

These disturbances burden city employees with significant stress and personal risk and may burden the institutions with costs for private security. Thus, MACRO has seen significant demand from such institutions, representing 9% of the lifetime service contacts it has made.

This points toward a potential future where MACRO might offer more value. We outline a set of possible changes that might help MACRO to deliver far more benefit to the community at much greater efficiency.

1/ Perform a rigorous problem analysis

Such an analysis should focus on the questions outlined in the previous section which are the basis of MACRO’s current goals. In the urgency to act during the turmoil of 2020, such an analysis was not performed, it was assumed.

We cannot stress enough how important it is to revisit problem analysis with rigor and impartiality toward needs and solutions. As Steve Jobs said: “If you define the problem correctly, you almost have the solution.”48

2/ Alter the target recipient population

MACRO’s current policies prioritize service to the homeless population, in part, to meet racial equity objectives. But addressing homelessness issues do not currently consume the bulk of police response time, even for calls where a sworn officer is not needed. Nor do BIPOC homeless persons constitute the largest portion of the BIPOC demographic that may experience negative impacts of policing. Analysis of 2019 call data, and recommendations of the RPSTF, suggests MACRO could have a much greater impact if it were to address police work beyond its current scope.

Presently MACRO diverts only 0.4% of calls serviced by police and could divert a maximum of 1.29% of serviced calls under current policy. By contrast, the CAHOOTs program (upon which MACRO was based) diverts 3-8% of police calls.49 If MACRO expanded to include all of the call types recommended by the RPSTF,50 it could potentially handle as much as 8.5% of police calls and 16.5% of police service load.

But to make such a change requires that MACRO reconsider its racial equity mandate because access to MACRO services will be distributed more broadly across the community, including to housed people, White people, and Asian people in proportions that will more likely reflect population demographics rather than a priority on unhoused BIPOC people, in particular.51

This is the approach used by the CAHOOTS program upon which MACRO was based. CAHOOTS does not focus on racial determinants for service delivery.

3/ Fold MACRO in with the civilian police staff

We must think carefully about an approach that diverts more policing to non-police agencies. Police servicing of non-violent, non-emergency calls affords them the opportunity to serve the community in lower-stress situations. If Police were properly staffed and supported for such activities, it could increase positive interactions between police and the community and counteract negative historical patterns.52 Conversely, if more such calls are taken away from the police, it may have the unwanted side-effect of degrading police-community interactions by saddling them with only the most confrontational and violent situations.

Thus, an alternative to expanding MACRO’s scope is to increase the staffing of the Oakland Police Department so they can better serve such non-violent needs. Even the Urban Strategies Council, in its feasibility analysis of MACRO, recognizes that OPD is understaffed by 33%.53 This additional staff need not be just sworn officers. Rather, some could be civilian police employees hired at the same pay scale as MACRO responders. This approach would allow use of existing police service, reporting, and dispatch infrastructure, likely saving overhead expense. And if it is done with proper training on procedural justice, behavioral health, and understanding of historical social context, it might begin to reframe the role and relationship of police in the community.

4/ Respond with one MACRO staff member, not two

MACRO currently deploys a pair of responders to each call, while OPD typically deploys a single officer on patrols. This MACRO operating configuration destroys much of the cost efficiency projected by its advocates. It basically doubles the cost of MACRO services unnecessarily, since MACRO calls are, by design, non-violent and non-emergency. A single person could be deployed to the situation to resolve it and call-in support only as needed. The fully burdened average annual cost of a single junior police patrol officer is $242K, and for two MACRO responders it’s $250K—i.e., it’s an increase in cost per hour for a tandem MACRO response.

5/ Do not set up a MACRO direct phone line

MACRO has been trying for a year to establish its own call dispatch operations and phone line when both already exist within Oakland Fire. This was presumably done based on the guidance of advocacy groups who said that BIPOC communities are afraid to call 911,54 and who sought to direct funding toward alternatives operated by those same groups.

However the Urban Strategies Council survey of model programs in other cities suggested residents do not want multiple numbers to call for service.55 Adding independent dispatch to MACRO will add significant overhead costs in training, technology, management and reporting, and may also add to complexity and confusion in a tripartite dispatch system of Fire, Police and MACRO.

Thus, MACRO would obtain significant cost savings and operational effectiveness by handling calls within current dispatch systems, which includes a Fire Dispatch center already handling over 70,000 calls annually. The pilot program already showed that this works and is a negligible additional load on OPD and OFD dispatchers.

6/ Stop providing unwanted street-side palliative care

Another significant expense for MACRO is repeated on-view calls to homeless individuals that result in no resolution of homelessness or health issues. Such calls could be discontinued unless MACRO is empowered with the tools and training to resolve the situation (if such tools and training are not duplicative with homeless and mental health services already provided by other agencies).

7/ Take a case-management approach to service delivery

Resolving most mental health or drug incidents will require resources that only Alameda County Health and Oakland Police can provide. Ultimately, this requires a case-management approach wherein the identified individuals are systematically managed through rehabilitation via the coordination of social services.

While taking such an approach might make MACRO more effective in addressing quality of life issues, it also would appear to be largely redundant with the mandate of existing services like the Alameda County Mobile Crisis Team (MCT), Mobile Evaluation Team (MET), Community Assessment and Transport Team (CATT).56 Before committing to such an approach, it is necessary to closely examine if and why such existing service providers could not do this job.

9. Where do we go from here?

When Elliott Jones stood up at the Public Safety Committee meeting in September, one thing stood out besides the report itself: his heartfelt desire to make MACRO work and to help the people of the City. And we believe that most everyone involved in establishing the pilot program had the best of intentions.

But good intentions do not assure good outcomes. The only path to good outcomes is hard-work, struggle, clear-eyed performance assessment, and the humility to adapt to reality as it is.

MACRO was a pilot program. And because that program has not been evaluated by the City,57 it remains a pilot program. By definition, a pilot recognizes that the motivating idea, or its implementation, may not work. Failure is an option. Otherwise we are being disingenuous to call it a pilot.

Whatever might be one’s opinion of MACRO, it did not demonstrate that it achieved its goals. If it has failed, we must accept that. If it can be fixed, we must fix it. If cannot be fixed, we must put the monies to better use.

When we avoid hard decisions, the people that suffer the most are always the people with the least.

Thank you to many members of the community for discussions, information, and critical feedback.

10 – Appendix

10.1 - Timeline of MACRO

2019-05-30 – Oakland City Council 2019 Report: A report highlighted CAHOOTS 30-year history in Eugene, focusing on non-emergency crises response by mental health professionals and EMTs, purporting to save millions in police costs by reducing police workload.

2020-07 – Budget & Budget Amendment: Oakland's City Council allocated $1.85M for the FY 2020-2021 budget to seed the formation of MACRO, and called for a 50% reduction in the the Oakland Police budget. It also funded the formation of the RPSTF to recommend additional options to achieve a 50% reduction in police funding.

2020-09 – Urban Strategies Report: City Council receives a report from the Urban Strategies Council who was commissioned to analyze the feasibility and design of a proposed MACRO program based on the CAHOOTS program in Eugene Oregon.

2020-12 – Council Resolution 88433: Oakland City Council directs the City Administrator to begin exploring options for creating MACRO with oversight by the Department of Violence Prevention.

2021-03-02 – Motion from Council Member Kaplan: Urged the City Council to expedite establishment of MACRO and transfer it from a contracted service under the Department of Violence Prevention, to a City-staffed function within the Oakland Fire Department.

2021-03-16 – Council Resolution 88533: Directed the City Administrator to begin implementing the MACRO pilot program and identify funding for it.

2021-04 – Council Resolution 88576: Allocated funding to create MACRO within the Fire Department by establishing its five racial equity and cost saving goals, and authorizing funding to hire the Program Manager.

2021-05 – Council Resolution 88607: Prioritized twelve recommendations from the Reimagining Public Safety Taskforce aimed at reducing the police budget by 50%. Expansion of MACRO beyond the initial funding allocated in the 2020 mid-cycle budget was the top priority among the twelve.

2021-07 – Council Resolution 88784: Increased the FY 2021-2023 budget for MACRO by $10M in response to receiving a $10M grant from the State of California for the program.

2022-04 – MACRO Grant for Equipment: MACRO received a $734K federal grant for equipment.

2002-04-09 – MACRO operations begin: MACRO responder units are sent out to make On-View calls to community members because 911 call transfers and mechanisms for community requests are not yet active.

2022-08 – MACRO begins accepting dispatch call transfers from OPD

2023-09 – MACRO report on expansion: At the Public Safety Committee Meeting MACRO estimates that a direct phone line will be established in Q1 of 2024, and that expects to make offers to fill 20 remaining positions for responders by November 2023.

2023-10-09 – MACRO Pilot Program completes: As of December 2023, neither MACRO or the City has assessed whether it delivered on its five mandated goals.

10.2 - OPD Dispatch Call Volume Data

Files with OPD call data may be accessed here:

Table 2: Count of OPD Dispatch Calls in 2019. Categorized by type, response, and requirement for a Sworn Officer. This data is the same as Table 1, but with the hierarchy of Responded and Sworn Officer Required swapped.

Increase in OPD Call volume since 2017. Call counts include emergency calls to dispatch and non-emergency calls. Source: November 2023 MACRO report from OPD to City Council.

10.3 - OPD Community Caretaking Stops

Community Caretaking represented 13.8% of all OPD stops. Of those Caretaking stops, 68% resulted in 5150 actions which reflects the nature of mental health calls received by dispatch (priority 1 and 2).

Table 3: Reasons for and result of stops made by Oakland Police Department (OPD) in 2022.58

The figure below shows the priority of all calls handled by OPD Dispatch in 2019 and whether those calls were MACRO-eligible. Priority 1 calls are defined as those that include potential danger for serious injury to persons, prevention of violent crimes, serious public hazards, felonies in progress with possible suspect on scene. Priority 2 calls are defined as urgent but not an emergency situation, hazardous / sensitive matters, in-progress misdemeanors and crimes where quick response may facilitate apprehension of suspect(s). Priorities 3, 4, and 5 calls include a variety of non-emergency assignments.

The following figure shows the priority of all mental health calls handled by OPD Dispatch in 2019.

10.4 - Additional Q&A

What is the cost of MACRO? If it’s $9 million per year, why is it so much more expensive than Eugene’s CAHOOTS program per citizen?

CAHOOTS costs $800K/year to service 3-8% of police calls. We do not have a financial analysis of CAHOOTS costs, so we can only speculate on why their costs are about ten times lower than Oakland’s budget for MACRO.

Judging by the overall police budget and population of Eugene, the cost of living in Eugene may be three times lower than Oakland. Or it may be that because CAHOOTS contracts its services to a private non-profit, it doesn’t have the pension and benefit obligations of the City of Oakland. The fully burdened cost of Oakland employees is about two times their salary. Thus, applying these factors to Oakland’s budget, gives $9M / 3 / 2 = $1.5M. Also, Oakland is 2X larger than Eugene. So divide again by 2, and you get $750K—which is the CAHOOTS budget.

Another question is why CAHOOTS argues that it relieves millions of dollars of police and emergency costs (roughly 15% of policing costs), when it is serving 3-8% of calls?

Additional data from Eugene would be required to address both of these questions adequately.

Is there evidence police aren’t sending over calls that would be MACRO appropriate?

No, all indications from Oakland Fire and MACRO show that OPD is collaborating. Moreover, Chief Armstrong was supportive of MACRO.

KTOP Recording of Informational Report on MACRO Operations by Elliott Jones, Oakland Public Safety Committee Meeting, September 26, 2023. https://oakland.granicus.com/player/clip/5708?view_id=2&redirect=true&h=4f354bd49fd43bae7f412e53dbe9a0f3#:~:text=0613%20Subject%3A%20Informational-,Report,-On%20MACRO%20Program

Budget Amendments - Notes and Errata, from Council President Rebecca Kaplan and Council Member Nikki Bas, July 21, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1L1BcMenaspTGJJBlgnhHR58FLb1Cg3iP

Memorandum on MACRO Pilot Program, Melinda Drayton, Interim Fire Chief & Ian Appleyard, Director HRM, March 15, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=15x7ziJFDHgKnK_HMNWe_7oDT2HFY5EwE

Oakland Reimagining Public Safety Task Force (RPSTF) Report and Recommendations, pp. 4-5, https://drive.google.com/open?id=19iznKLQ-3raf8iW2WG9AVtyow2TQWhQo

Wren Farrell, Don't want to call the cops? In Oakland, you can call MACRO (Pt. 1). https://www.kalw.org/2023-12-05/dont-want-to-call-the-cops-in-oakland-you-can-call-macro

Budget Amendment MEMO, from Council President Rebecca Kaplan and Council Member Nikki Fortunato Bas, July 21, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Lckv-fdt2ZOgcZxuyIuPJttYtMLpn96J

Explanation of the Exhibits to the Resolution Amending the FY 2020-21 Midcycle Budget, from Finance Director Alan Benson, July 2, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1L8AMCPwkTYMMIZ21Qel9w3JoCZGMIK7g

Council Resolution 88269 CMS, establishing the Reimagining Public Safety Task Force, July 28, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1M4JLnPaJiZ2HDOM0Tjg4fV8tQ3TC6U8v

RPSTF Report and Recommendations. https://drive.google.com/open?id=19iznKLQ-3raf8iW2WG9AVtyow2TQWhQo

Reimagining Public Safety Recommendations Prioritization Memorandum. Councilmember Carroll Fife and Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas, April 30, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1MPIxnH2HPjKacvuE7LD9XgwovVcMfbqY

Council Resolution 88607 CMS, May 3, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1MPegUxjGksvLnlFU9W7vBIgw8MsPvXJG

Letter to RPSTF Steering Committee, December 7, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=19r_zsuyctZE6HVXEpPn9hROhQ_ABI2Ji

Urban Strategies Council, Report on Feasibility and Implementation of a Pilot of Moblie Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACRO), reported to Oakland City Council in September 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16bGTq58ssJ5vBAruRIqd3HjXl1nOiHpU

Oakland City Council Resolution 88553 CMS, March 16, 2021, p. 3. https://drive.google.com/open?id=18rmBvSKL5jMH7UBiWAJVehn5YcznnY2Q

RPSTF Report and Recommendations, p. 243, suggested MACRO could save Oakland Police $25M/year. https://drive.google.com/open?id=19iznKLQ-3raf8iW2WG9AVtyow2TQWhQo

Council Resolution 88576 CMS, April 2021, establishing the MACRO Pilot Program, operating parameters, and goals.

Urban Strategies Council Report, p. 7. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16bGTq58ssJ5vBAruRIqd3HjXl1nOiHpU

Oakland City Council Motion, March 2, 2021, p. 3. https://drive.google.com/open?id=17Q7DRVbqlS3L46f51gQkXIe7ZUbvJPtK

Memorandum on MACRO Pilot Program, Melinda Drayton, Interim Fire Chief & Ian Appleyard, Director HRM, March 15, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=15x7ziJFDHgKnK_HMNWe_7oDT2HFY5EwE

Reimagining Public Safety Recommendations Prioritization Memorandum. Councilmember Carroll Fife and Council President Nikki Fortunato Bas, April 30, 2021, p. 4. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1MPIxnH2HPjKacvuE7LD9XgwovVcMfbqY

Oakland City Council Motion, March 2, 2021, p. 3. https://drive.google.com/open?id=17Q7DRVbqlS3L46f51gQkXIe7ZUbvJPtK

RPSTF Report and Recommendations, Recommendation #57, p. 156. https://drive.google.com/open?id=19iznKLQ-3raf8iW2WG9AVtyow2TQWhQo

Council Resolution 88553 CMS, March 16, 2021, p. 3. https://drive.google.com/open?id=18rmBvSKL5jMH7UBiWAJVehn5YcznnY2Q

MACRO Report to City Council from Reginald D. Freeman, Chief Oakland Fire Dept., September 1, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16v_sxcFuMaDBfuuORcWWKaaA4DX47ovD

Council Resolution 88784, July 2021, authorizing a budget increase of $10M funded by a state grant. https://drive.google.com/open?id=18y-VPl4473zDyiiRNF7IJ8JsUUjslvgZ

Council Resolution 88576 CMS, April 2021, establishing the MACRO Pilot Program, operating parameters, and goals. https://drive.google.com/open?id=14zzUmH9ceNF6hudWPsJ2967wKmtjQcpF

RSPTF Report and Recommendations, Recommendation #57, p. 156. https://drive.google.com/open?id=19iznKLQ-3raf8iW2WG9AVtyow2TQWhQo

City Budget Data obtained via public records request: https://oaklandca.nextrequest.com/requests/23-12137. Formatted and summarized data download: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-9BoZvHLFeYl94M-rRXdjB4FKwBoM9UD

Alameda County Behavioral Health (ACBH) operates a variety of crisis services and Mobile Crisis Teams to respond to individuals in the community experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. https://www.acbhcs.org/acute-integrated-health-care/acute-crisis-services/

Alameda County’s $2.5 Billion Home Together 2026 Community Plan: This comprehensive plan to address homelessness includes various components like shelter beds, affordable housing, and homelessness prevention efforts, including $340 million from 2018-2021 to aid individuals and households in obtaining or maintaining housing..https://therealdeal.com/sanfrancisco/2022/05/11/alameda-county-plans-to-spend-2-5b-to-address-homelessness/

The current annual funding received from city, county, state and federal sources totals approximately $183 million, which is less than half of the annual requirement to meet the Home Together goal. https://homelessness.acgov.org/report-archive.page

Project Roomkey Expenditure: During the pandemic, Project Roomkey used $102 million to provide shelter to over 5,000 people, with a significant proportion moving to permanent housing later. https://www.courthousenews.com/despite-funding-influx-california-homelessness-crisis-grows-in-alameda-county/

Wren Farrell, Community Responders: Oakland’s Alternative to the Police, KALW, December 2023 https://www.kalw.org/community-responders-oaklands-alternative-to-the-police

Memorandum on MACRO Pilot Program, Melinda Drayton, Interim Fire Chief & Ian Appleyard, Director HRM, March 15, 2021, p. 6. https://drive.google.com/open?id=15x7ziJFDHgKnK_HMNWe_7oDT2HFY5EwE

Example of 5150 response by police in 2023. Naked woman on freeway, https://www.nbcbayarea.com/news/local/video-naked-woman-running-gun-bay-bridge/3281664/

Example of a MACRO contact that was assisted by Police, Fire & Medical. Quoted from MACRO April 2023 report to City Council. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1E0IjdY29MAuuUFAHUPPbazp9uno-VZ87&usp=drive_fs

Collaboration with the Police to Safely Deescalate a Behavioral Episode April 27, 2023

MACRO was approached by a community member (CM) who was screaming and pacing back and forth and walking in and out of the street. MACRO engaged from the vehicle for safety reasons, asking them to stay on the sidewalk. The CM stated that he needed to go to the hospital pointing at his hospital wrist band stating, "I need to get back to summit". There were no apparent injuries or illnesses stated by the CM. MACRO 6 then requested an OPD Response because the community member was putting not only himself but others around him in danger by staying in the middle of the street and not complying with instructions by MACRO responders. MACRO then stayed in the vehicle and monitored the situation as the CM remained pacing back and forth in the bus lane in the street. Approximately 10 minutes later an OPD officer (Unit 1538) arrived on scene and appeared to be familiar with the CM. MACRO CIS engaged with the officer and explained the situation. The Officer was able to calmly ask the CM to come to the sidewalk to which the CM complied. Shortly after, another officer, FALCK unit and Engine company 13 arrived on scene. Shortly after OPD engaged with him, he got into the ambulance with no resistance. MACRO 6 then left the scene. There were no injuries to any community members or responders on scene. MPTA.

Additional detail on the depth of training and certification required for handling 5150 situations in California is provided in this training manual from Riverside University Health System. https://www.rcdmh.org/Portals/0/PDF/Inpatient/RUHS-BH%205150%20Training%20Manual%20rev%20May%202018%20(final)%2030APR18.pdf

Wren Farrell, Building Trust, one person at a time (Pt. 3) December 2023. https://www.kalw.org/2023-12-07/building-trust-one-person-at-a-time

MACRO contact statistics were extracted from the monthly MACRO reports and compiled for analysis. Data available for download: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-7E7GVGxEpJ8Flgz7h6klLXzhXPnJXuR/edit#gid=689241245

Informational Report to the Public Safety Committee, September 26, 2023. https://drive.google.com/open?id=18u-l5EukqcHWH1hwgeTAA_WueYDRsaLk

Oakland Police Department Calls For Service data, 2019. https://www.oaklandca.gov/documents/calls-for-service

Center for Public Safety Management, Police Data Analysis Report, Oakland, California, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1KvXHBjiU2cn-0CQXvWVAMEeYwM2u_8ei

MACRO - Call Type Quick Guide. https://cao-94612.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/documents/Fire-Police-Communication-MACRO-Dispatch-Guide-v.2-08.2022.pdf

CAHOOTS website, accessed December 17, 2023. https://www.eugene-or.gov/4508/CAHOOTS

FY ’23-’25 budget data for Oakland Police Department obtained from https://oaklandca.opengov.com/ Download summarized initial budget data (before cuts): https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1CGoy6RBBbJ3QIdku0aR1iDoUQ45pZdNg and staffing cuts approved in July 2023: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1C3n09a5cvGIcqZqe7DyCZQES-bl0-Fc1

MACRO staffing data for 2023, obtained by public records request: https://drive.google.com/open?id=1HTQw0qcO5A3ymQzO_3Lb4CbN51VSNh34

Overall OPD Dispatch call volume has increased by 32% in 2023 compared to 2019 (per November 2023 MACRO report from OPD to City Council, https://drive.google.com/open?id=1Gt6WS63QJ2lShGSP-XoUPkgpKC-oJtYS). Moreover, the homeless population in Oakland has also increased since 2019. Thus, it is likely that MACRO-eligible call volume has increased. But to err on the side of optimism, we use 2019 dispatch volumes in our calculations, which will likely result in an over-estimate of MACRO savings by low double-digit percent.

MACRO budget vs. actuals data obtained from City of Oakland Finance Department per public records request: https://oaklandca.nextrequest.com/requests/23-12137. Download summarized data: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-9BoZvHLFeYl94M-rRXdjB4FKwBoM9UD

MACRO Report to City Council from Reginald D. Freeman, Chief Oakland Fire Dept., September 1, 2021. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16v_sxcFuMaDBfuuORcWWKaaA4DX47ovD

Wren Farrell, Building Trust, one person at a time (Pt. 3) December 2023. https://www.kalw.org/2023-12-07/building-trust-one-person-at-a-time

Monthly acceptance rates ranged from 11% to 27% across the 18 month pilot program. See data in MACRO contact statistics. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1-7E7GVGxEpJ8Flgz7h6klLXzhXPnJXuR/edit#gid=689241245

MACRO 1 year report, April 2023. Download: https://drive.google.com/open?id=14kyPK5ASYmEQmwDsdRfnWmIJDPStQHaK

Alameda County Behavioral Health (ACBH) operates a variety of crisis services and Mobile Crisis Teams to respond to individuals in the community experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. https://www.acbhcs.org/acute-integrated-health-care/acute-crisis-services/

Informational Report to the Public Safety Committee, September 26, 2023. https://drive.google.com/open?id=18u-l5EukqcHWH1hwgeTAA_WueYDRsaLk

It’s not clear if Steve Jobs actually said this, but every source that we could find across the internet attributes it to him.

Proposed MACRO-eligible call types defined in Center for Public Safety Management, Police Data Analysis Report, Oakland, California, 2020. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1KvXHBjiU2cn-0CQXvWVAMEeYwM2u_8ei

Equal access to opportunity or resources does not assure equal outcomes. Therefore, equity policies often favor certain groups in order to distribute outcomes according to targeted racial or identity proportions.

A randomized controlled trial in New Haven Connecticut found that positive contact with police, delivered via brief door-to-door non-enforcement community policing visits, substantially improved residents’ attitudes toward police. https://news.yale.edu/2019/09/16/study-finds-community-oriented-policing-improves-attitudes-toward-police. Author’s note: This citation was added on 29 Dec 2023, after the date of publication on 26 Dec 2023.

The Urban Strategies Council Report recognizes that “studies of staffing based on population, crime, and call volume suggest that OPD should have 1200 officers yet has fewer than 800.”, p. 6. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16bGTq58ssJ5vBAruRIqd3HjXl1nOiHpU

Recommendation #58 of the RPSTF final report (p. 238), and priority #2 of Council Resolution 88607 was to transfer 911 call center out of OPD and place it in the MH First (Mental Health First) program operated by APTP. APTP is a member of the Defund Police Coalition, which advocated for these recommended policies and for funding of the MH First program (see part 2 of recommendations cited in RPSTF page 238).

Urban Strategies Council Report, p. 26. https://drive.google.com/open?id=16bGTq58ssJ5vBAruRIqd3HjXl1nOiHpU

Alameda County Behavioral Health (ACBH) operates a variety of crisis services and Mobile Crisis Teams to respond to individuals in the community experiencing an acute behavioral health crisis. https://www.acbhcs.org/acute-integrated-health-care/acute-crisis-services/

It would be more appropriate for an independent entity like the City Auditor to evaluate MACRO’s performance.

OPD Stop Data obtained from https://www.oaklandca.gov/resources/stop-data

This is an enormous amount of work and incredibly valuable to the city and its residents. Thank you so much for taking the time, and for presenting the data so clearly.

This is a great analysis, and another example of Oakland‘s dysfunctional administration of resources and failure to manage based on results. It’s part of the systemic failing of our city government, whose officials are disengaged with the concept of seeking to better our city in tangible ways