Oakland's city employee counts show a dramatic shift in service priorities over five years

Public safety staff declined by 206 employees (-12%), and other departments added 336 employees (+13%). Police are slated to bear the majority of forthcoming cuts.

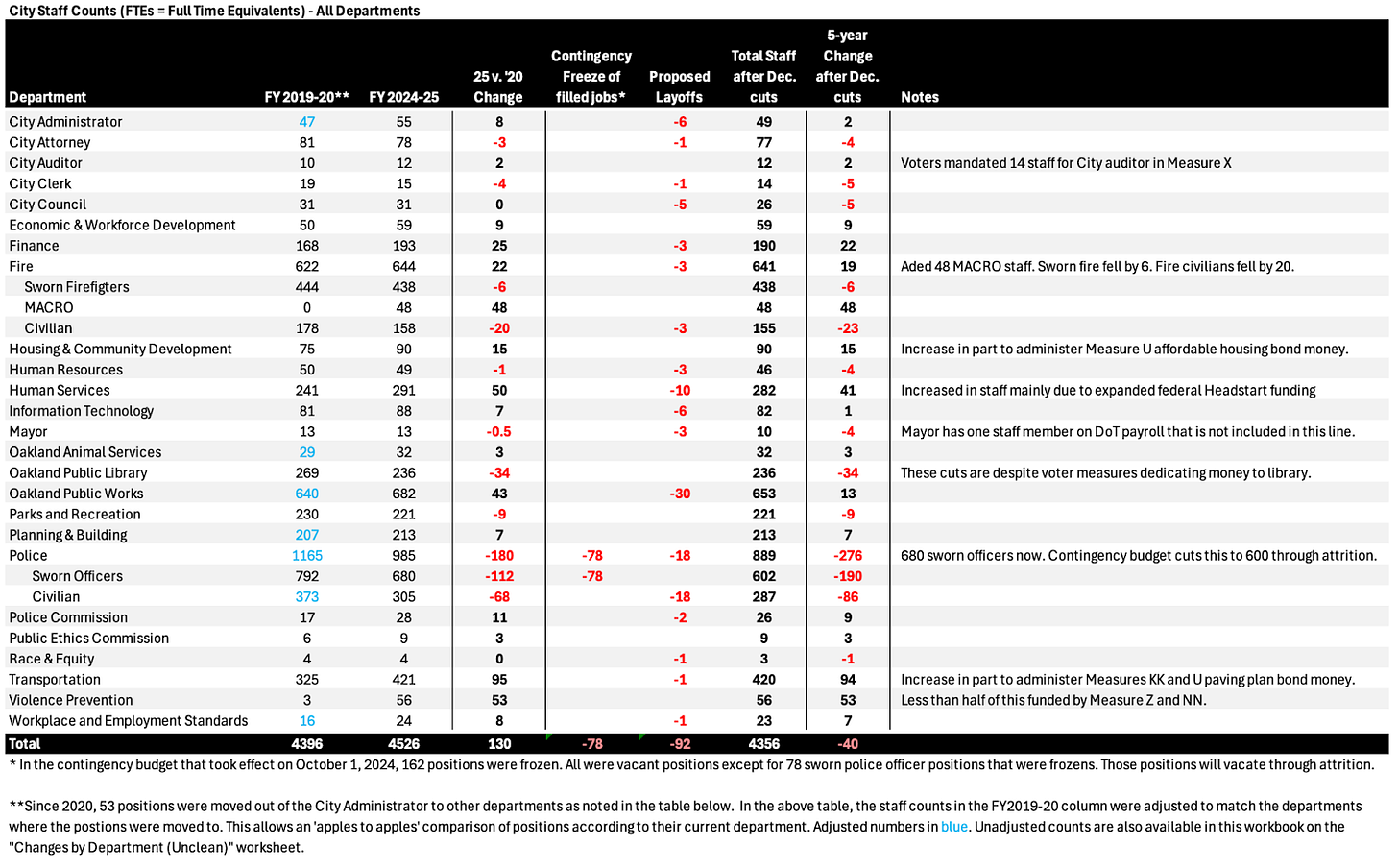

On December 5, the City of Oakland released a list of employee counts for the past five years, itemized by department and job function.

The city cut 180 police and 26 fire personnel, while it increased staff in other departments by 336 employees, including major increases in Transportation, Public Works, MACRO, Violence Prevention, and administrative departments.

With proposed additional cuts, public safety will have lost a net 304 employees over five years (-17%), of which 276 are police cuts. Other departments will have added a net 264 employees (+10%).

Despite the cuts, the city still does not have a sustainable plan to balance the budget in ensuing years.

Today, December 17, the city intends to vote on a series of sweeping budget resolutions and ordinance changes, including one-time use of restricted fund balances and an emergency declaration that allows the city to add new tax proposals to the April special election ballot.

The justification for these actions is the long-running budget crisis—one that the city notes is a consequence of uncorrected over spending since 2020:

Unfortunately, this crisis is largely the result of continued over expenditures and the on-going structural imbalance that began in 2020. It’s important to acknowledge that while this situation is difficult, it wasn’t caused by an unexpected external event.

One of the contributors to this overspending is expanded employee count and wages. For the first time, the city released employee counts for every city department. This new data shows where services expanded and contracted over five years, and who are the winners and losers in the proposed additional cuts.

Public safety (police and fire) was cut by 206 positions over the past five years, while 336 new employees were added across all other departments. Expansions included creation of the MACRO program and Department of Violence Prevention (DVP), together adding 101 new staff.

Overall, public safety staffing declined 12% to 1,581 employees (civilian and sworn), and all other departments rose 13% to 2,945 employees. Net, 130 employees were added to city payroll over five years.

How will the budget proposals change city staffing?

The city is proposing to focus the majority of further cuts on public safety. It argues it is cutting departments in proportion to their share of the General Purpose Fund (GPF). But police and fire departments are funded almost entirely by the GPF, while many other departments get only 1.3% to 35% of their funding from the GPF. Thus the cuts to police and fire are disproportionately larger, relative to their overall budget, than departments which receive a small fraction of their funding from the GPF.

The rationale for the disproportionate cuts to public safety are likely motivated by other factors. Some council members have a vested interest in protecting MACRO ($10M/year) and the Department of Violence Prevention ($25M/year), whose creation they championed. These programs and staff were left untouched in the budget cutting. The choices also appear to be influenced by the lobbying of public employee labor unions whose “roadmap” for balancing the budget is included in the city's official budget recommendation package. This roadmap argued that police spending was the major cause of the budget shortfall, and that police needed to take the bulk of budget cuts.

The final budget recommendation package, to be voted on Tuesday, cuts 96 police, 3 fire, and 74 non-safety staff. After these further cuts, public safety staff will have declined by 304 employees in five years (-17%) while all non-safety departments will maintain a net increase of 264 employees (+10%).

In addition to the police staff cuts, the city is mandating that the police eliminate $25M of overtime spending, but does not specify which services the police should cut to meet these objectives. Most likely this will include suspension of special operations like sideshow and violence suppression, community interactions such as neighborhood council meetings, and reduced patrol staff.

The city also plans to close (i.e., “brown out”) 6 of its 25 fire stations. These closures will likely eliminate most or all of the fire department’s $34M of overtime spending currently needed to staff these fire stations. They will likely not result in sworn firefighter reductions.

Combined, the staff and overtime cuts could eliminate nearly $100M per year of ongoing public safety expenditures. But it also places public safety at risk. In the proposed declaration of emergency, the city notes:

Curtailing critical essential services such as law enforcement and the fire department, including paramedic services, risks increasing response times in criminal cases, cases of medical emergencies, fires, accidents, or natural disasters will impact the safety, health, and welfare of its residents.

How will this impact public safety?

A reduction in 6 stations is about 25% of fire services. Since 80% of fire calls are actually medical responses, it is likely to result in delayed attention to urgent medical needs. It will also increase response time significantly for fires. In both cases, that could mean more fatalities, injuries, and damage to property.

For police, the impacts are likely to be even more extensive. Sworn police count is slated to decline through attrition to 600 officers. This was made possible because the city council suspended the minimum officer counts that are mandated by voter measures Z and NN. In addition, 89 of those officers are out on medical, administrative or military leave, leaving about 510 sworn officers to serve a city of 430,000 people.

As noted in the city’s supplemental revenue and expenditure report, the police are compensating for understaffing with increased overtime to cover patrols, special operations, court appearances, training requirements, and Negotiated Settlement Agreement (NSA) requirements. With the elimination of overtime, police will need to significantly reduce patrols as well as special operations including violence suppression and sideshow suppression, and some reduction in Ceasefire operations. Bureaucratic requirements, including court appearances and NSA reporting cannot generally be avoided without disciplinary actions, and will likely receive priority at the expense of patrol and community activities.

MACRO and Department of Violence Prevention activities will not be impacted by budget cuts, but the City is eliminating the safety ambassador program (currently performed on contract by outside vendors).

How will it address the ongoing deficit?

In addition to the proposed layoffs and overtime reductions, about $80M of the $129M of proposed budget cuts come from one-time moves. These include fund transfers that drain restricted fund balances, such as the self-insurance fund, the affordable housing trust fund, library funds, a portion of the emergency reserves, and others.

These continued one-time moves not only weaken the city’s financial foundations and curtail services, they mean the city will likely be back in this deficit crisis within the next 4 months. As the city notes in its declaration of emergency:

The City has considerably reduced operational and maintenance expenditures to close the budgetary gap. However, these actions are a one-time solution as the City continues to face a structural imbalance where recurring expenditures continue to outpace recurring revenues.

The city appears to be betting that the ongoing deficit will be addressed by making the cuts in public safety permanent for the foreseeable future, while maintaining current spending on all other services. And the city hopes to supplement these safety cuts with $20 to $80M of new restricted-fund tax measures, including $21M revenue raised from increased sales tax.

These bets assume the public will entrust the city with more tax revenue, even though it has failed to responsibly manage prior taxes in accordance with voter mandates. And it is betting that residents can tolerate the negative impacts on crime, fire and emergency medical response resulting from the current public safety cuts, while maintaining its faith in city leaders’ stewardship of the community.

The success of those bets may also depend on continued ad hoc subsidies provided to Oakland by the state of California in the form of dedicated CHP patrols. Though the number of officers committed by CHP is unclear, the impact has been noticeable. As of the last report, 1200 arrests were made by CHP, almost a quarter of OPD’s typical annual amount. But it is unclear whether the state will continue to subsidize and supplement Oakland’s declining spending on policing.

There is also a major additional factor not addressed in the present budget cuts—the city’s contracts with labor unions expire in June. If unions demand annual above-inflation raises, as they have for the past several years, it could add $40M a year in further spending increases. Discussions of compromise have not even started.

And finally, there are the escalating costs of pensions and health spending, which are expected to total $192M next year—a $21M annual increase over this year. The city notes in its budget recommendations that these long-term employee obligations are on an unsustainable course.

While the present budget maneuvers may get the city to the end of the year without a bankruptcy, the city’s future solvency remains at risk because it still has not enacted sustainable spending priorities.

Appendix

Tabulation of employee staff counts by department. Click to enlarge or see spreadsheet view. The table below includes FY 2019-2020, and FY 2024-2025 (current year) employee counts. It also shows the impact of further cuts by department. Additional details, including job-specific staffing changes and services provided by the department are included in the spreadsheet. Data obtained from Supplement A of the City’s amended revenue and expense report.

Tags: Budget, Policing, Public Safety

This is all so deeply irresponsible :( Can a new mayor reverse all this? What are the reasonable boundaries on what they can/could do?

"Some council members have a vested interest in protecting MACRO ($10M/year) and the Department of Violence Prevention ($25M/year), whose creation they championed. These programs and staff were left untouched in the budget cutting."

They don't work weekends and don't log hours. Not ness. a scam, but def washing the money and not preventing crime, violence, etc.