“Our officers have been conditioned to do as little as possible—to stay out of trouble”

Zealous investigations of Oakland police officers have created a downward spiral of morale and performance

At a January Police Commission meeting, Oakland Police Chief Floyd Mitchell described what he called the “weaponization of the discipline process.”

"If you make a mistake in the Oakland Police Department… you are going to get allegations levied against you that will ruin your career and your opportunity to work anywhere else in the United States. Our officers have been conditioned to do as little as possible—to stay out of trouble. And that is a problem."

Mitchell’s remarks highlight concerns that excessive disciplinary measures are discouraging proactive policing and negatively impacting officer performance.

Oakland’s police oversight policies have led to an excessive number of disciplinary investigations of officers, even for minor infractions—far more than any other city we examined. 92% of officer investigations are not “sustained,” meaning that the allegation was untrue, within policy, or lacked evidence. Of those that are sustained, 75% are for minor offenses such as use of profanity or conducting personal business while on duty. Nonetheless, they become part of an officer's permanent personnel record, the police logs, and supervisory files, and cast a long shadow of fear over officers.

These policies are directed by the twenty-year old Negotiated Settlement Agreement (NSA) and enforced by a federal monitor. Oakland Police Department (OPD) is required to commit resources and time to excessive investigations for all complaints—even those that are trivial, untrue or are better served by simply addressing officer performance through management and mentorship. This results in 6 to 19 times more investigations than comparable cities. And minor offenses must be escalated to major investigations if a “pattern of misconduct” is identified—though no clear definition of a pattern exists. Moreover, supervisors themselves can be disciplined for not identifying such ill-defined patterns. This can result in escalation of allegations to major cases by supervisors who are trying to protect themselves from the oversight apparatus.

The net impact is a disproportionate number of investigations and disciplinary actions against officers compared to other cities, negatively affecting morale, recruitment, and overall policing effectiveness. Moreover, this high investigatory burden drains inordinate resources from OPD and taxpayers—costing supervisors as much as 80% of their time, and costing the department millions of dollars in additional investigatory costs.

Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) experienced similar problems from 1998 to 2001 when a change in policy forced them to investigate every allegation of misconduct.1 A University of Chicago study showed that the excessive scrutiny of LAPD officers led to officer disengagement, less proactive policing, and significant decline in public safety. In LAPD’s case, the federal judge intervened to reform the oversight, resulting in a restoration of department morale and effectiveness within two years.

But in Oakland, after twenty years of federal oversight, OPD remains in a cycle of heightened discipline, with no apparent path to compliance, and no willingness by the federal monitor to take a critical look at the impact of his actions on police, police effectiveness, and public safety.

Oakland’s present approach to police oversight focuses disproportionately on investigation and punishment as a means to achieve just and fair policing. In this prosecutory miasma, even unintentional mistakes can result in an arduous investigation and disciplinary action, with no opportunity for mentorship or remedial training for improved performance.

Investigation and punishment of police misconduct is a necessary component of just law enforcement. But Oakland’s all-punitive approach to police oversight offers no pathway to build a more capable, more effective police force that Oakland residents need. Without policy reforms, officer morale and performance will remain low, and public safety will continue to suffer.

OPD disciplines officers two to ten times more often than other cities

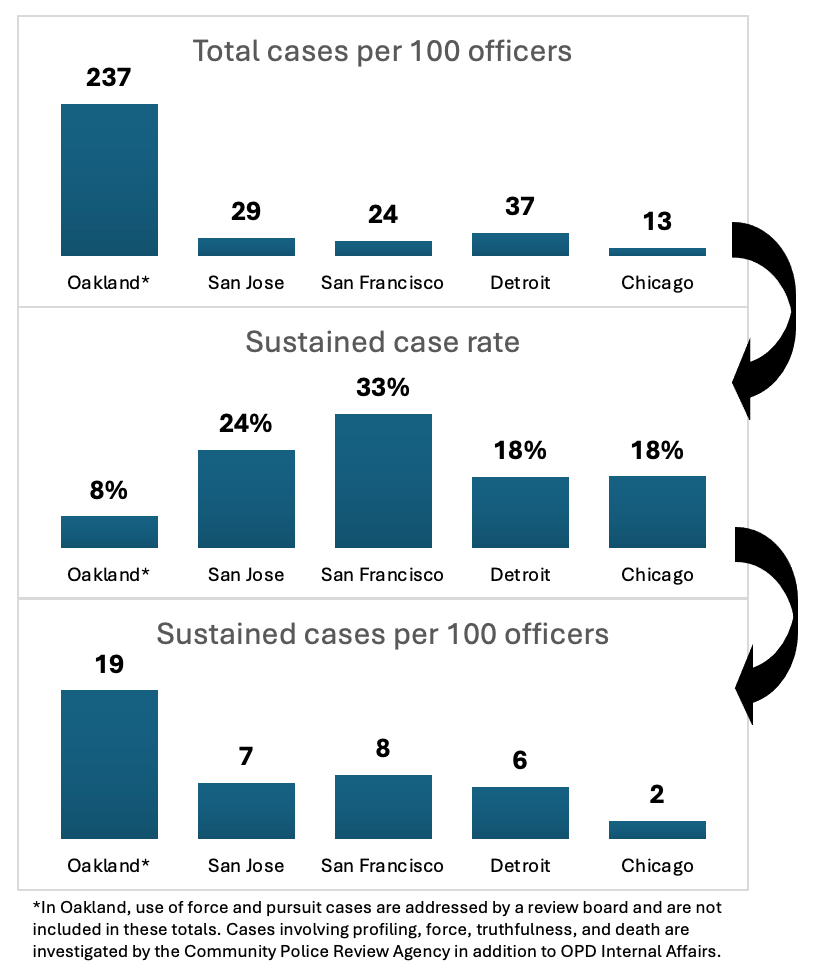

OPD’s disciplinary policy results in 6 to 19 times more formal investigations of civilian complaints (cases) than San Francisco, San Jose, Detroit and Chicago (Figure 1). It also has the lowest rate of sustained findings after investigation (8%) compared to other cities (18 - 33%), meaning that 92% of complaints are found to be untrue or not provable.

Despite this low sustainment rate per case, OPD’s exceptionally high case count results in nearly 20% of the OPD officers receiving disciplinary action each year. That’s far higher than other cities. And 75% of those disciplinary actions are for minor offenses.

Minor or not, a sustained finding is recorded on an officer’s permanent file, affecting promotion eligibility and future employment opportunities with other law enforcement agencies. This heightened scrutiny has led to low morale, increased inaction, and recruitment challenges for OPD.

What drives OPD’s high rate of officer investigations and discipline?

Since January 2003, Oakland has been under a Negotiated Settlement Agreement (NSA), which mandates police reforms including policies and procedures to handle complaints and officer discipline. Under the NSA, all complaints about police conduct from any source must be investigated.

The NSA stipulations are a major driver of OPD’s high case load. In other cities, minor cases can be diverted from a formal investigation to an informal resolution process where a supervisor oversees corrective actions to address the complaint. But in OPD, this informal resolution process is limited in its applicability.

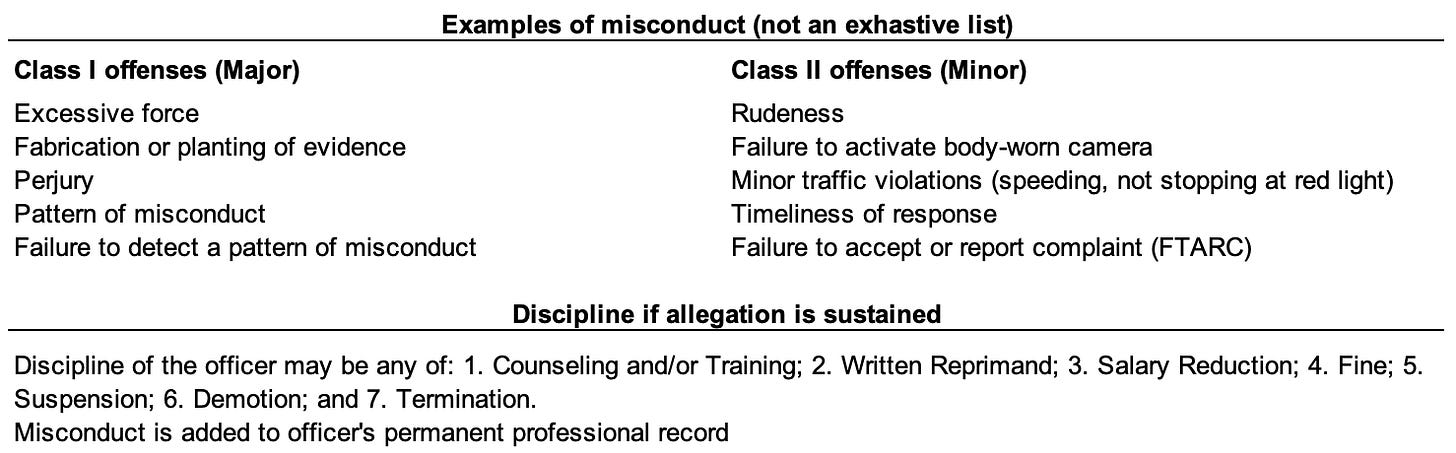

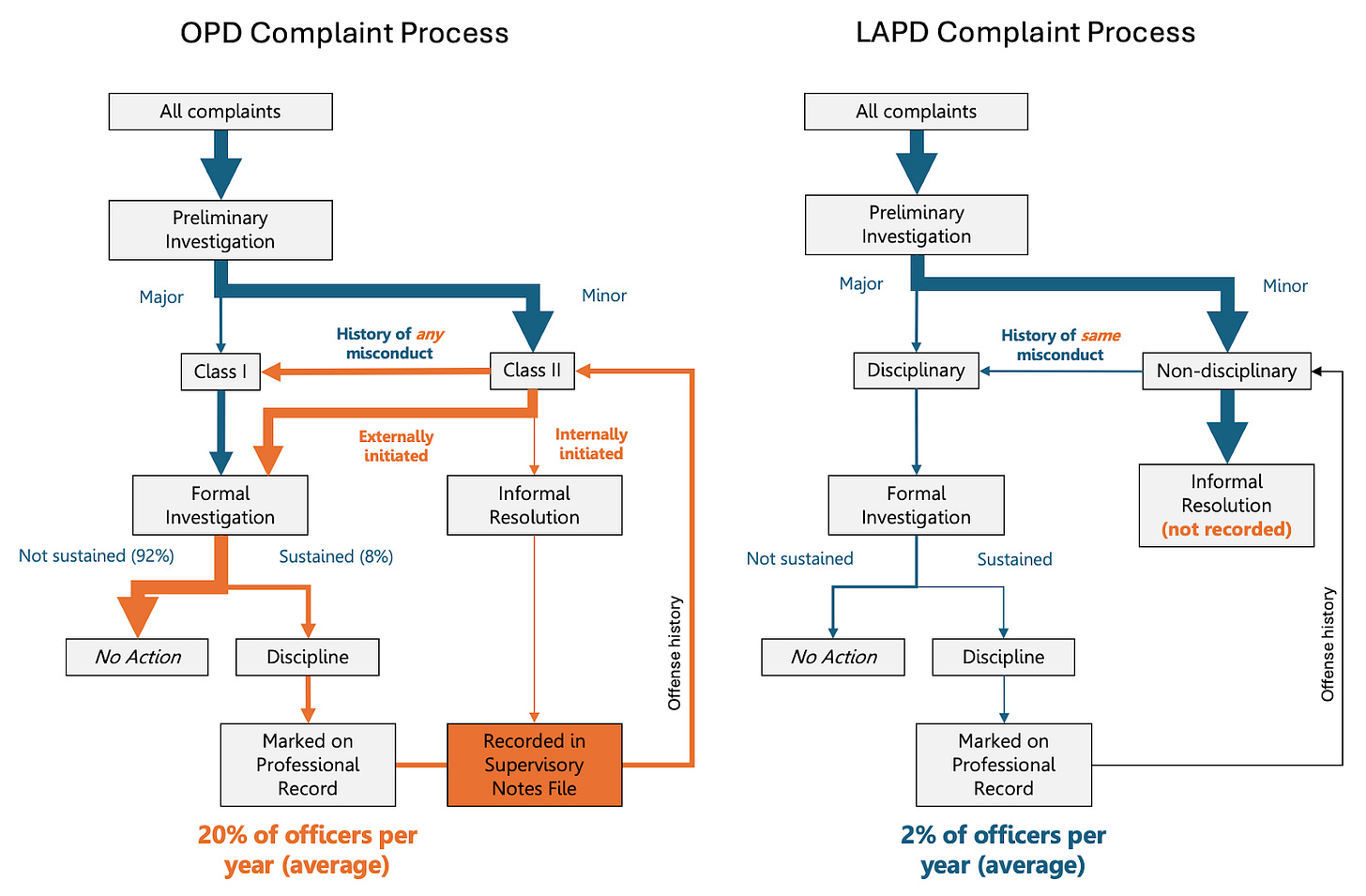

As directed by the Department General Order M-03, the OPD complaint process begins with preliminary investigation to classify the complaint as Class I (serious misconduct) or Class II (minor misconduct), or to close the case if it is deemed insufficiently clear or specific or is withdrawn by the accuser. All cases then proceed to formal investigation.

If a finding is sustained2 it is added to the officer’s permanent personnel record which is used in promotion decisions and transmitted to new employers. Otherwise, it is not added to the permanent personnel record, but is tracked in OPD’s internal Chronological Activity Log and Supervisory Notes Files for officers. These internal records are often used as the basis for pattern recognition of officer conduct.

There are two exceptions to this default path for complaint handling. The first may be used if a Class II complaint originated internally within OPD staff3, and the officer has no prior “pattern of misconduct.” A supervisor can close such cases, and resolve them through an informal resolution process that may include discussion with the accuser, training, or mentorship, instead of formal discipline. Informal resolution is recorded in the Supervisory Notes File, but not added to the officer’s permanent personnel record.

The second exception occurs if the supervisor observes a “pattern of misconduct.” They must escalate the Class II case investigation to Class I. Failure to do so is defined as Class I misconduct, and will result in an additional case filed against the supervisor themself. Thus, to avoid prosecution for missing a possible pattern, some supervisors escalate Class II complaints to Class I disciplinary investigations even if there is little evidence of a pattern.

Moreover, neither the NSA nor OPD policy explicitly defines what constitutes a “pattern of misconduct,” leaving it to the judgement of supervisors and case investigators. Officers can be investigated based on a history of even one prior offense. Combined with a supervisor's own fear of discipline, the threshold for declaring a “pattern” is low. For example, if an officer is accused of swearing during a traffic stop and, in a separate complaint, is cited for excessive speeding, these two incidents could be used to justify a Class I investigation just the same as a more severe allegation such as the planting of evidence.

Once the disciplinary escalations begin, offenses begin to accumulate on an officer's record, driving a self-fulfilling loop of escalating disciplinary actions for conduct that could have been resolved through the informal complaint resolution process.

In other cities, minor offenses are addressed, by default, through the informal process not investigations. This allows concentration of investigative resources on major cases, while allowing supervisors to focus on training, mentoring and policing effectiveness.

But in OPD, both Class II and Class I investigations follow the same strict procedures of investigation for every case. That includes evidence gathering, interviews, report writing, reviews by internal affairs, reviews by the chain of command and the Chief of Police, a disciplinary committee meeting, and due process if disciplinary recommendations are made. After many months, the officer receives their written reprimand or suspension from someone unfamiliar with the specific offense and with no interest in mentoring the officer toward improvement. The result is excessive effort spent investigating minor issues, drawing resources away from major misconduct cases and away from mentorship to correct minor ones.

When discipline goes too far

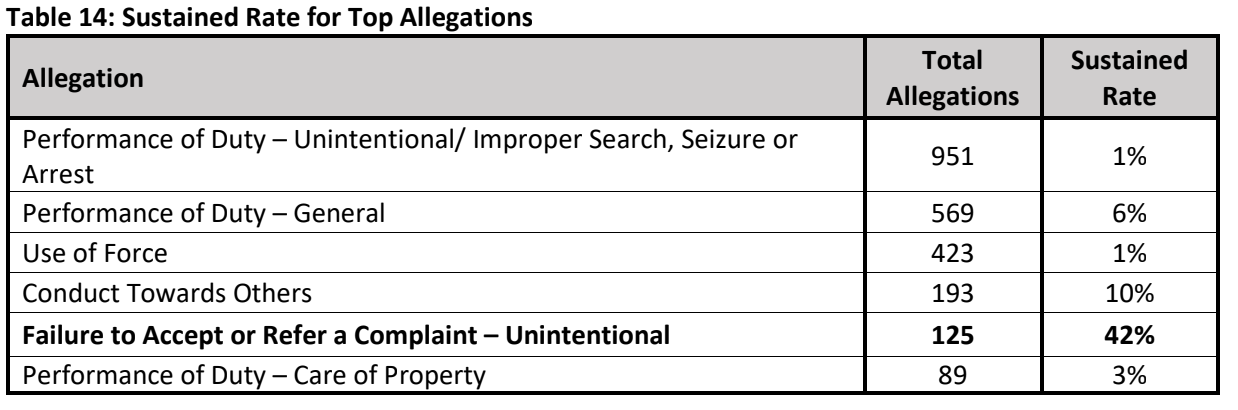

The impact of OPD’s escalatory cycle of punishment is underscored by OPD’s 2023 annual analysis of complaint investigations, which called-out excessive disciplinary action for the minor allegation of unintentional Failure to Accept or Refer a Complaint” (FTARC). Investigators sustained 42% of cases filed for FTARC. In comparison, investigators sustained only 1% of major allegations related to improper search, seizure or arrest, and 6% of allegations related to general performance of duty. This outsized share of disciplinary action for FTARC is a direct outcome of the escalatory disciplinary process.

OPD supervisors, middle managers, and internal affairs personnel were so afraid of themselves being accused of “missing something” that they interpreted the meaning of “complaint” as broadly as possible. Even throw-away remarks by people who weren’t even interacting with the officers (bystanders) would be considered a “complaint.” And any officer who failed to report such “complaints” were then investigated for FTARC misconduct.

Ironically, this situation led to the federal monitor, Robert Warshaw, to extend OPD’s oversight in 2023. He judged that the policy—which itself was instituted to comply with federal oversight—was driving racial disparities in the discipline of black officers. But his judgement was incorrect. As shown in the 2023 analysis, the disparity was actually caused by differences in the number of prior offenses by officers, and therefore necessitated different punishments in accordance with OPD’s procedure manual.

Regardless of its true cause, the monitor’s perception of racial disparities finally motivated him and the police commission to approve a change in the policy on FTARC. The policy now permits such offenses to be addressed with the informal resolution process instead of disciplinary proceedings. In addition, it removes the requirement to ask clarifying questions if the officer is unsure about whether the citizen would like to make a complaint. But OPD’s general policy on “patterns of misconduct”—which drives the escalatory discipline process and contributes to the high case load—remains in place.

Lessons from LAPD—how excessive oversight hurts morale and public safety

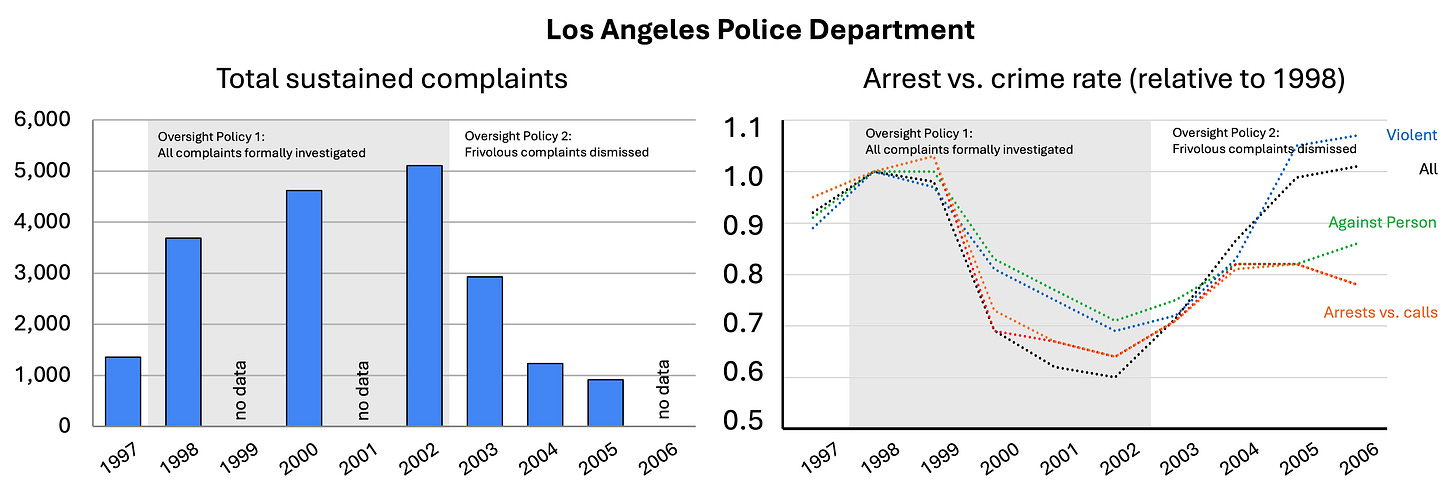

A decline in officer morale due to heightened disciplinary scrutiny was previously observed in the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD). In 1998, LAPD changed their discipline policy in the wake of its own corruption affair, the “Rampart scandal”. In order to cut down on corruption, the department required that all complaints against an officer would trigger an investigation. This change led to longer investigation times, delayed promotions, and lower morale; 9 out of 10 officers agreed that “fear of discipline prevented them from proactively doing their jobs.”

Then in 2001, LAPD came under federal oversight to improve documentation of police activities and formalize use-of-force policies. The department was required to complete investigations within five months—a challenging target given the large backlog of open cases. A year later, due to a backlog of over 9,000 cases that was hindering implementation of the federal consent decree, the federal monitor revised the complaint policy. Only more serious complaints would be formally investigated, while minor complaints were addressed through corrective action at the supervisor level.

This heightened scrutiny had significant public safety implications. A 2021 University of Chicago study of LAPD found that the rise in investigations and discipline resulted in a decline in arrest activity, and reversal of the policy restored arrest activity.

LAPD’s federal oversight ended in 2013. Today, LAPD investigates roughly nine times fewer disciplinary cases per officer than OPD, according to the California Department of Justice.

Following the reforms, LAPD’s policies differed from OPD in that non-disciplinary complaints (equivalent to OPD Class II cases) are not investigated unless there is a clear pattern of similar behavior for which the officer is being accused. Minor infractions (most cases) are addressed only through the informal non-disciplinary process and corrective action—confidential actions that are not added to permanent personnel records. LAPD only pursues formal investigations and disciplinary action in serious cases (equivalent to Class I cases at OPD).4

The hidden costs of increased investigations

OPD’s investigatory burden has several downstream effects in addition to its impact on morale. Currently, OPD has 542 open investigations. According to OPD policy, all complaint investigations (Class I and Class II) must be completed within 180 days. This was monitored by the federal monitor in Task 2 of the NSA which requires more than 85% of cases to be completed in this timeframe.

This large caseload demands a significant amount of officer time to prosecute the investigations. Approximately 80% of cases are "division-level investigations" handled at the supervisor/sergeant level. And about 80% of a sergeant’s job is consumed by administrative duties, including investigating citizen complaints, as noted in a recent Police Commission meeting. Due to these policies, sergeants are spending more time at their desks rather than in the field. In times when the department is understaffed, this investigative load results in higher overtime costs to sustain basic operations.

The high volume of pending cases also extends the duration of administrative leave for officers, partly due to pending Skelly hearings, which must be conducted before disciplinary action can be imposed. Currently, there are 149 pending Skelly hearings and 42 officers on administrative leave. Eleven officers have been on leave for one to two years awaiting Skelly hearings, costing the department nearly $3 million annually.

OPD’s emphasis on disciplinary measures creates an environment where punitive actions are prioritized over constructive feedback and skill improvement. Without adequate training and support, officers may even repeat mistakes, leading to a cycle of escalating complaints, discipline, and disengagement—instead of growth and elevated performance.

OPD’s misguided policies are jeopardizing Oakland public safety

In LAPD a federal monitor helped turn the department around in just one year. In contrast, Oakland’s federal oversight has now exceeded 20 years with no end in sight.

Recent reports from Oakland’s federal monitor, Robert Warshaw, continue to find OPD out of compliance, a state of affairs facilitated by his frequent altering of compliance requirements—effectively “moving the goalposts” in realtime.5 Additionally, vague and subjective criteria, such as the need for “cultural change” are used to justify ongoing oversight.

Despite Warshaw’s extensive experience in other jurisdictions and fifteen years as the federal monitor for Oakland, his actions appear to disregard the impact on officer morale, police effectiveness, and public safety.

Oakland’s current civilian oversight bodies have also failed to address the issue of overzealous investigations. At a recent Oakland Police Commission meeting, former Community Police Review Agency director Mac Muir acknowledged the extensive disciplinary process within OPD, but then dismissed the notion that it could harm officer effectiveness and public safety:

"I want to make sure it’s clear that there’s an extraordinary level of due process. There are so many checks and balances in the disciplinary process that I can understand the feeling of not wanting to get in trouble. This is a place where you can get in trouble—there are a lot of rules. But that doesn’t mean our crime rate is higher because of that feeling. That’s called having a tough job."

Current OPD policies focus on disciplinary action, rather than performance and remediation. These policies do not foster a learning culture, where one is permitted to learn from errors and improve. They foster a culture of control and punishment—a kind of internal surveillance state.

As a result, supervisors are buried under an unproductive investigatory burden, draining time away from field mentorship, patrol operations, and community engagement. And officers retreat from their duties, fearing that any action or inaction might be a trigger for investigation.

As Chief Mitchell stated:

“I associate it with a pet or dog that constantly got hit over the head with a newspaper. Sooner or later all you have to do is pick up the newspaper and that dog is cowering down because it’s afraid it's going to get hurt. It’s hurting our city because our officers are afraid to do their job.”

Oakland’s complaint investigation policies diminish officer morale, department performance and public safety. But LAPD showed that such negative impacts can be reversed quickly with thoughtful reforms. It’s time for OPD to do the same.

The next Case Management Conference about the NSA with senior district judge William Orrick is scheduled for 3:30 pm on May 6 at the San Francisco Courthouse, 450 Golden Gate Ave, San Francisco.

Tags: Public Safety, Crime, Police, Policing, NSA, Federal Oversight

Glossary

Allegation — A claim or charge that someone has done something illegal or wrong.

Arrest-to-crime rate — Ratio of number of arrests to number of crimes per population size.

Case — An investigation into one incident to assess allegation(s) of misconduct. In police data, each investigation is counted multiple times, one for each officer involved in the case. In addition, one or more allegations may be associated with each officer in a case. For example, in 2023, there were 691 investigations at OPD involving 1648 officers and 2680 allegations.

Complaint — Allegation of misconduct.

Discipline — Types of actions such as suspension, termination or demotion.

Exonerated — There is sufficient evidence that alleged conduct did occur but is within law and policy.

Misconduct — Actions that are violation of laws, departmental policy or ethical standards.

Non-discipline — Corrective measures such as conflict resolution discussions, training, or counseling.

Not sustained — Investigation did not disclose sufficient evidence to determine whether or not alleged conduct did occur.

Skelly hearing — Pre-disciplinary hearing that is part of due process.

Sustained — Case or allegation is supported by evidence, justifying disciplinary action.

Unfounded — There is sufficient evidence that the alleged conduct did not occur.

Supervisory Notes File — A log of for each officer’s performance that is maintained by their supervisor. It records both improper behavior and exemplary performance.

When any Class I or II investigation concludes, it results in one of four findings: Sustained, Not Sustained, Exonerated, Unfounded. A sustained finding is added to the officer's permanent personnel record. All other outcomes are added to OPDs Chronological Activity Log and the Supervisory Notes File, and can be used to justify “patterns of misconduct”.

OPD policy requires that all external complaints are investigated, even if it is an officer’s first complaint, unless the accuser choses the informal resolution process.

Comparison of OPD and LAPD complaint processes. Key differences highlighted in orange. Note that Class I in OPD is equivalent to Disciplinary in LAPD, and Class II is equivalent to Non-disciplinary. Two key differences drive the ten-times higher disciplinary rate in OPD: (1) any prior offense tends to be treated as a pattern of misconduct, and (2) all externally initiated complaints receive formal investigation. These differences drive a self-fulfilling loop of accumulating prior offenses and escalating disciplinary actions for even minor offenses.

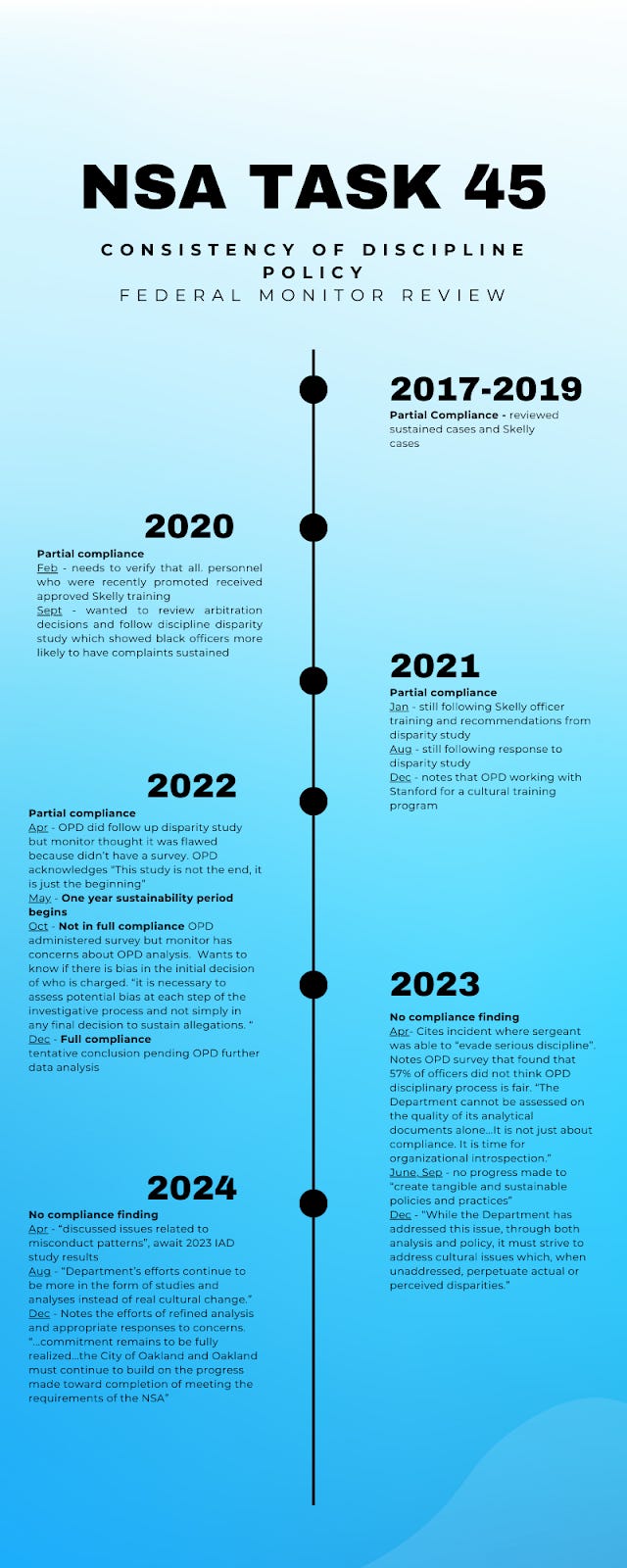

Timeline of the Independent Monitoring Team reports and Sustainability Period reports for Task 45 by the federal monitor Robert Warshaw

Thanks for another example of your superb work and painstaking analysis. Please keep it coming,

Thank you. Very detailed and informative. The answer, as always in policy, is to maintain a balance. The history of racial injustice in the US makes it difficult but not impossible. Oakland an extreme case. But imbalance is clearly not an option. Nobody wins, everyone suffers. Will our dysfunctional democracy be able to maintain balance?