The Pamela Price recall petition was certified—what happens now?

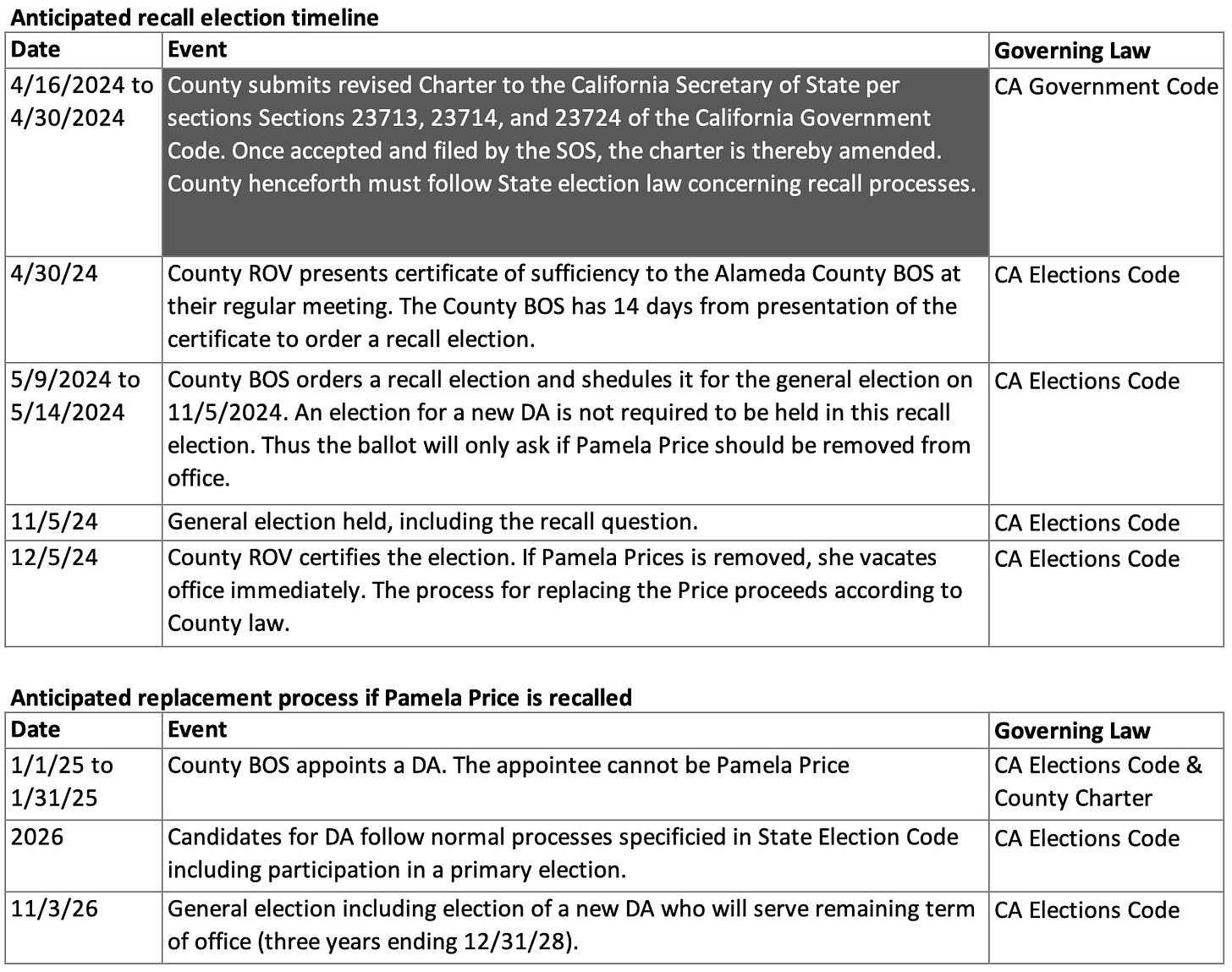

The recall election will likely occur on November 5, 2024. If Price is removed, the Alameda County Board of Supervisors will appoint a replacement to serve until the November 2026 general election.

The Alameda County Registrar of Voters (ROV) has completed its count of signatures on the Pamela Price recall petition, and has certified that the number of valid signatures is sufficient to place the recall question on the ballot. The ROV counted 74,757 valid signatures according County Charter requirements. A minimum of 73,195 valid signatures was required.

Voters soon will be asked:

Shall Pamela Price be recalled (removed) from the office of Alameda County District Attorney?

But when will that vote happen? What if voters say yes? Who will replace Price and for how long? How will that person be selected?

Here is how it will likely play out:

The recall question will be placed on the November 5, 2024 general election ballot. There will be no choice of replacement candidates on the ballot.

If a majority of voters choose to recall Pamela Price, then she will have to leave office immediately.

The DA position will remain vacant until the Alameda County Board of Supervisors (BOS) appoints a replacement. That will likely happen in the first or second BOS meeting in January 2025. Pamela Price cannot be appointed to the role.1

The appointed DA will serve until the next election, at which time voters will choose a new DA. If the County does not call a special election, the next general election is November 3, 2026. Thus the appointed DA could serve for up to 2 years.

The newly elected DA will serve to the end of the current term (December 2028). After that, DAs will be elected to standard four-year terms.2

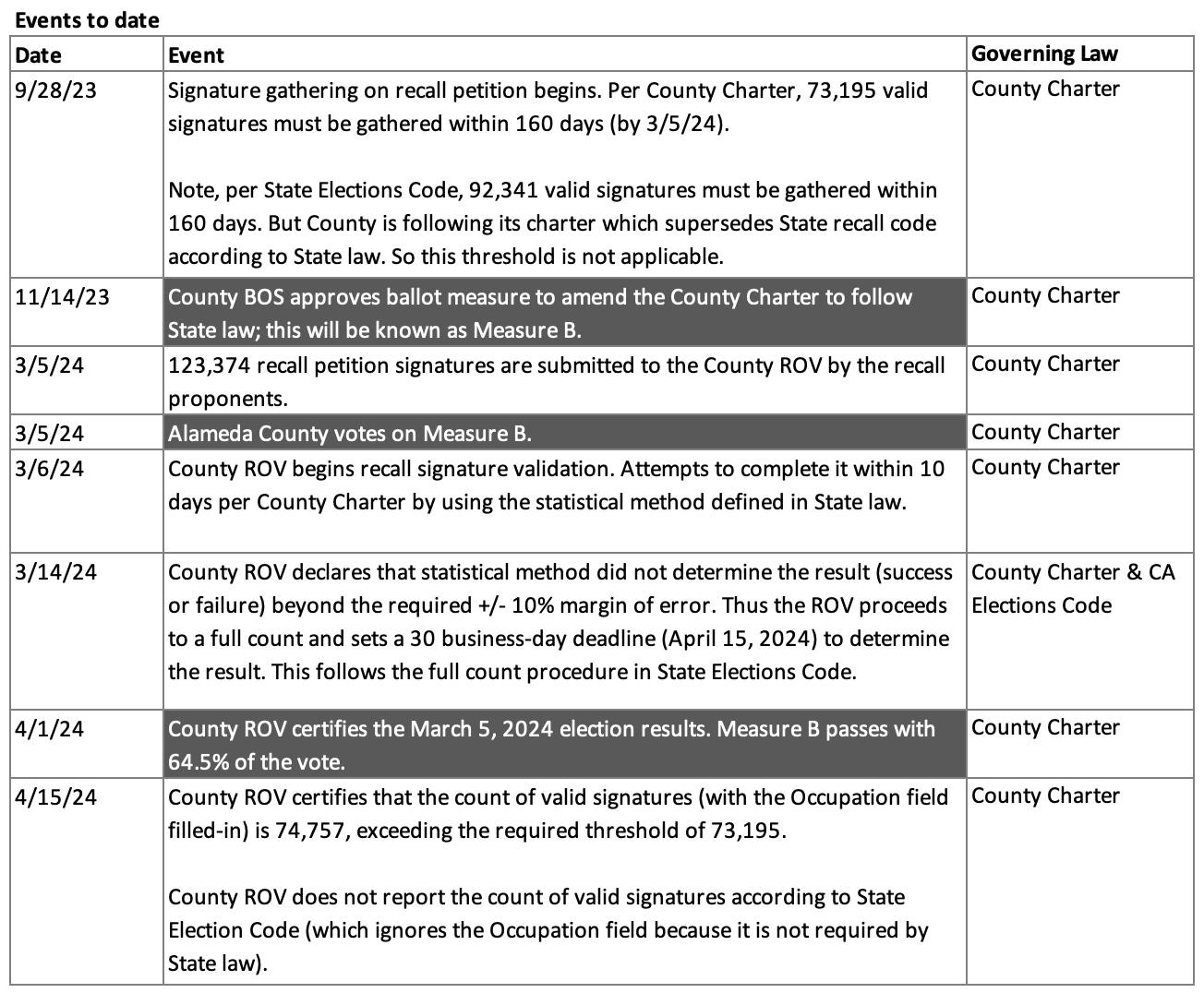

Why is this the likely timeline? The answer is somewhat complicated because the recall process spans a change in the Alameda County Charter concerning recalls.3 That change was approved by voters on March 5, 2024. The recall process began five months earlier on September 28, 2023 and will continue after the change in County Charter.

We break-down the recall process, the impact of the change in law, key issues, and some of the complaints about the process that have been argued by Pamela Price and her supporters. We also provide a complete timeline of past and anticipated future events in the recall.

A tale of two codes

There are presently two sets of laws governing recalls in Alameda County—the County Charter and the State Elections Code. Some provisions of those codes are in conflict, and one provision of the recall section of the County Charter violates the US Constitution.4

In general, County law supersedes State law concerning the recall of County officials, provided of course that it does not conflict with the State or Federal constitutions. And wherein County law is silent, State Election Code will govern. Thus, in principle, these conflicts should not impair a recall.

However, the County Charter’s recall procedures are 98 years old, and some elements of the County Charter are nearly impossible for the ROV to follow procedurally. This creates issues for the County irrespective of any conflicts of law. For example, the nominating process for replacement candidates is longer than the time period allotted for scheduling the recall election; and the counting period for signatures is too short given the current population of Alameda County.

In any event, these conflicts and practical issues will be resolved soon because the Alameda County Charter will be revised to fully follow State law on recalls. Voters approved this change when they passed Measure B on March 5, 2024 with 65% approval. The change in Charter will take effect sometime in the next few weeks when Alameda County submits its revised Charter text to the California Secretary of State (SOS), and the SOS accepts and files it.5

Prior to the revision, the County was following the County Charter provisions for recalls. After the revision, the County will follow the State procedures. In practice, that means that the recall petition process followed the former County recall laws because it was executed before the revisions took effect. And the recall election will likely follow State recall law because the election will be ordered by the Alameda County Board of Supervisors sometime in the next month, presumably after the revisions take effect.

How are the County and State recall laws different?

We highlight a few key differences in these two sets of laws, and how they impact the recall.

Number of valid signatures to qualify. According to County laws, 73,195 valid signatures are required to qualify the petition for the ballot (15% of County votes for all candidates for the office of the Governor at the last election). The ROV certified 74,757 valid signatures. Thus, the ROV issued a certificate of sufficiency and will deliver it to the Alameda County Board of Supervisors at their April 30, 2024 meeting. Thereafter, the recall process will continue as described below.

On the other hand, the State Election Code requires a threshold of 92,341 valid signatures (10% of registered voters). Based on the statistical sampling data provided by the ROV in March, it is likely that the petition will also clear this higher threshold.

How is that possible if only 74,757 valid signatures were counted by the ROV? The ROV is currently following County law, and therefore only counted signatures with the Occupation field filled-in (more on that below). But the State Election Code has no such requirement. Thus, an estimated 20% more signatories were rejected by the ROV by following County law than would be rejected if it followed State law.

If there are lawsuits over which rule set should be followed, and State law prevails, then the ROV will need to report a new tally that includes the signatures with a blank Occupation field. If a sufficient number signatures are found to be valid, the pending recall election would continue as planned. It would not necessarily alter the timeline for the recall election, as noted in the final section of this article.

Time period to count signatures. Under the former recall provisions of the County Charter, the ROV is required to determine sufficiency of signatures within 10 days of their submission by the petitioner. Signatures were submitted on March 5, 2024, and thus a determination should have been made by March 15.

But the ROV was unable to complete its count of the recall petition signatures within 10 calendar days as required by the Charter, because the statistical method employed by the ROV was insufficient to determine the outcome with certainty. The ROV chose to use a statistical method defined in State law because the County Charter is silent on the method of counting; thus the County had leeway to choose a method. The State method requires counting only 5% of the votes which is a much faster procedure than counting all signatures, and was potentially possible to complete in 10 days.

However, that method also requires that the estimated count exceed 110% of the required number of signatures in order to account for potential statistical sampling error. The statistical estimate was 75,624 valid signatures. Though that is more than the required threshold, it was insufficient to meet the requirements of the statistical procedure. Thus, the ROV invoked the State procedure for a full count of every signature within 30 business days.6 Those results were reported by the ROV today.

Timeline to a recall election. If sufficient validated signatures are counted to qualify the petition for the ballot, then the ROV must submit a certificate of sufficiency to the BOS “without delay.” The meaning of “without delay” is ambiguous, but it seems to imply the next regularly scheduled BOS meeting. At that meeting, the BOS would then order an election, and the ROV would have to hold a special election within 40 days.

Under the now-adopted State Election Code, the timeline changes. The ROV is specifically required to submit the certificate of sufficiency at the next regularly scheduled BOS meeting (no ambiguity on that point). The BOS then has up to 14 days to order an election. Thereafter, the County must set a special election to take place in 88 to 125 days, or consolidate the recall election with a regularly scheduled election within 180 days.

The next BOS meeting is April 30, 2024, and thus the BOS will have until May 14 to order an election. Because May 9 is 180 days prior to the November 5, 2024 general election, the BOS will likely wait until May 9 to order the recall election, and therefore it will be consolidated with the general election. The County will assuredly follow this path since the County estimates that a special election would cost $20M.

Vacating office if a recall is successful. According to County law, candidates to replace the recallee would be included on the ballot under the recall question, and the recallee is not allowed to be one of those candidates. Thus if Pamela Price is recalled, the voter-chosen replacement would immediately take office.

But according to State Election Code, Section 11382, only the recall question is presented to voters on a ballot for recall of local officers. No replacement candidates for office are presented. If Pamela Price is recalled by voters in the November election, she will be required to vacate the DA Office immediately after certification of the election results. The County has 30 days to certify the election, which places the date of vacancy on December 3 at the earliest. The office will remain vacant until a successor is appointed or elected.

Replacing a recalled official. According to State Election Code, Section 11382, the process for replacing the recalled officer proceeds according to “the law”, which in this case is the County Charter. The County Charter, Section 20 states:

Whenever a vacancy occurs in an elective County office, … the Board of Supervisors shall fill such vacancy, and the appointee shall hold office until the election and qualification of his successor. In such case there shall be elected at the next general election an officer to fill such vacancy for the unexpired term, unless such term expires on the first Monday after the first day of January succeeding said election.

Section 20 does not address whether a recalled candidate is allowed to be appointed back to the office from which they were just removed. The California Constitution and State Elections Code which governs in the absence of a specific County provision, resolves this issue. As noted in State Election Code, Section 11302,

A person who was subject to a recall petition may not be appointed to fill the vacancy in the office that he or she vacated and that person may not be appointed to fill any other vacancy in office on the same governing board for the duration of the term of office of the seat that he or she vacated.

Thus, the BOS would likely appoint a new DA in January 2025, and Pamela Price would be ineligible for re-appointment to the DA Office by the County BOS.

Regardless of when a new DA is appointed, candidates may file to run for the office in the next general election according to the normal processes specified in State Election Code. That would mean qualifying for the primary ballot in 2026, and then winning a top two spots to qualify for the general election.

A clean process despite the problematic County laws…well almost

The recall process has transpired relatively cleanly to date, given all the ambiguities surrounding County and State codes. And there should soon be a clean transition in governing law right at the interval between the petition portion of the process and the election portion.

Such a well-timed transition was not assured, even as the BOS agreed to place Measure B on the ballot. Had the timing of the recall petition and Measure B vote been different, the County might have been forced to call a special election within the 40 day window afforded it by the County recall procedure. And if it failed to meet that tight timing, neither State or County law prescribe an explicit resolution. Thus, the process could have degenerated into a kind of purgatory between County and State law, which may have to have been resolved in court.

That said, the process was not perfectly clean. As noted on March 14, the ROV was unable to complete its count of the recall petition signatures within 10 calendar days as required by the Charter. Thus it used the State procedure for a full count within 30 business days. Given that the County Charter is silent on what happens when the ROV fails to meet its mandated timeline, it was a logical decision to fall-back to State law for the counting process. But the ROV did not actually have an explicit basis in law to follow that extended timeline.

Thus, the County’s hybrid approach, which uses (a) County law for determining the number of required signatures and for validating them and (b) state law to determine the timeline and method for counting signatures, potentially leaves it susceptible to complaints and lawsuits over the process. In fact, Price has argued that if the County uses State law for the timeline of counting and the election process, then it must also use State law for signature validation and for the number of signatures to qualify the petition.

And regardless of this particular issue on counting, it is not clear if it is valid to switch governing law in the middle of an active recall process. Thus the County’s overall approach, to follow County law on the petition process, and State law on the election process, is open to scrutiny.

Points of contention

Recent elections at both local and national levels have shown that lawsuits are almost inevitable in hotly contested elections. And the Pamela Price recall is likely to be no exception.

The basis of such lawsuits need not even hold merit, because the goal is not necessarily to win. The value of a lawsuit is often strategic—to cause delays in the process, and to create doubt or confusion in the minds of voters (especially low-information voters). It can also create a rallying point for advocates and supporters; the lawsuit itself, regardless of its merit or adjudication, can be marketed as evidence of injustice. If that marketing is coupled with procedural delays and voter confusion, it can serve to erode support for the recall and build funding and supporters for its opposition.

Thus, such lawsuits are very likely to be filed by Pamela Price or her supporters, provided they have sufficient seed funding to execute them. We summarize some of the key points of contention that have been raised in the public sphere, and some of which may be used as complaints in a civil lawsuit against the County.

Validity of recalls. A common refrain of Pamela Price and her supporters is that recalls are undemocratic, and a conspiracy of election deniers and wealthy interests. But as the right to recall is enshrined in the Article II of the California State Constitution, claims that recalls are undemocratic or conspiratorial are untrue. Most likely, this complaint is promoted as a campaign tactic to sow doubt, and garner anti-recall support. It is unlikely to be used as the basis for any legal action.

Signature gatherers. Pamela Price has complained that it is illegal to use signature gatherers who are not registered voters in Alameda County. Signature gatherers used in this recall were over 18, as required by County and State law, but some were not County registered voters. This issue has already been decided by a US Supreme Court decision which found it unconstitutional to limit signature gathers to registered voters. Thus the County does not enforce this illegal provision of County code. And any lawsuit based on this argument would likely be dismissed quickly by a judge. The likely purpose of this complaint is also just campaign strategy.

Determination of valid signatures. There are three points of contention regarding the counting of valid signatures because County and State laws differ on this point.

County law requires that a person's Occupation be filled-in alongside the signature. The Occupation can be “none”, “N/A”, “No Occupation”, or anything else. But it cannot be blank according to County law. On the other hand, State law requires no information on Occupation. Thus, any response, or no response, is acceptable.

The time period for counting signatures differs: 10 calendar days for County law, and 30 business days for State law (and up to 60 under some circumstances).

The number of signatures required to qualify the petition differs: 73,135 according to County law and 92,341 according to State law.

The ROV is following a hybrid process that uses parts of both laws. While there is no prohibition against such an approach, there is also no explicit basis in law to follow it either. Thus, the methodology used for validating and counting signatures is likely to be a public complaint, and potentially a lawsuit.

Changing governing law. The County’s approach, based on California case law, has been to follow the laws currently in effect when executing the recall process. This approach means they will switch governing law from County to State in the midst of an active recall process. While this seems to be the logical approach and grounded in precedent, it is likely to be a point of complaint. It too may be brought by Pamela Price for resolution by the court.

What happens if lawsuits are filed?

If any of the above complaints were filed as lawsuits against the County, it seems unlikely to disrupt the timeline for a November recall election. Adjudication of the cases can proceed while preparations are made by the ROV for the recall election. While Pamela Price may request an injunction to stop such preparations, the request is unlikely to meet the extreme circumstances needed to grant relief. In particular, Pamela Price would not suffer irreparable harm on account of the preparations themselves; and the injury to public interest, if preparations were stopped, would likely outweigh any harms argued by Price. Moreover, should any lawsuit by Pamela Price succeed on merit, the recall process could be stopped at that time or results of a recall election invalidated, thereby avoiding any prospective harms. Thus, a court is unlikely to intervene with an injunction.

Although an injunction seems unlikely, a court case could potentially impact the execution of the recall. For example, the court might invalidate the ROV’s use of two sets of governing laws during the recall. A likely resolution would be a court order to use one or the other sets of laws in its entirety. As the recall petition has met County requirements, and would appear likely to have met State requirements, such an outcome would not likely halt the recall process. But it could alter its course of execution. In fact, if the former County recall provisions are mandated, it might even speed the recall election timing.

Correction, April 17, 2024: The original version of this article incorrectly stated that the next general election is in 2025. This was corrected in the present version to 2026.

Appendix

A detailed timeline of completed and anticipated future recall events is provided in this spreadsheet. The timeline shows three parallel processes: the recall procedures of the County, the recall procedures of the State, and the events to modify the County Charter itself. Also included are the data from the ROV from its statistical sampling of signature counts in March.

A simplified summary of the timeline is presented below.

Timeline of completed and anticipated recall events

References

State Elections Code, Division 8, Nominations (link)

State Elections Code, Division 11, Recall Elections (link)

Alameda County Charter, revised 2000 (link)

California State Recall Guide, revised January 2024 (link)

Alameda County Recall Procedures, downloaded April 12, 2024 (link)

Alameda County Pam Price Recall FAQs, published November 9, 2023 (link)

California Government Code, Chapter 5, County Charters (link)

Alameda County Election Results, March 5, 2023 (link)

Measure B - Ballot Measure Submittal Form (link)

Per the Alameda County Charter (Section 62, governing recalls), the recalled official is prohibited from running as a candidate in the recall election to replace her/himself. In addition, State Election Code Section 11302(b)(4) prohibits a recalled official from being appointed to the position they just vacated on account of the recall election.

The current term is an unusual six-year term due to a change in the election cycle that was effected in 2022 by AB759 which aligned elections for County officers to the Presidential election cycle.

The exact form of the question is mandated by the State Elections Code. Based on the passage of Measure B, Alameda County, the County Charter is in the process of being revised to align to State Elections Code. Thus, recall elections in Alameda County will henceforth follow the State Elections Code, not the recall procedures of the current County Charter.

US Supreme Court ruled in Secretary of State of Colorado vs. American Constitutional Law Foundation that it is unconstitutional to require circulators of a petition to be registered voters. Thus the Alameda County ROV does not enforce this provision of the County Code.

A change is County Charter goes into effect according to the procedure of California Governing Code Section 23724.

State law requires that signature counts must be completed within 30 days of the submission of signatures if a full counting is used, or within 60 days of submission if the statistical sampling method is used.

It also prescribes a method for counting by statistical sampling. First, a count of valid signatures is made using a random sample of 5% of the signatures. The proportion of valid signatures in the sample is assumed to be the same as in the full set of signatures, and the total number of valid signatures are estimated using that proportion.

If that estimate is more than 110% of the required amount, then the petition is declared to be successful; or if it is less then 90% of the required amount, then it is declared to be unsuccessful.

If the signatures are found to exceed the required threshold by either method, then a certificate of sufficiency must be submitted to the Alameda BOS at the next regular meeting.

Thank you, Mr. Gardner, for this extremely comprehensive, fact-driven, informative and wonky (that's a compliment) essay.

Excellent reporting. Keep it up.