Under DA Pamela Price, Criminal Prosecution Plummets in Alameda County

And criminal accountability has been eroded

Controversy has surrounded Pamela Price in her first year as Alameda County District Attorney—and the recent influx of State attorneys has amplified it. Some claim her leadership has contributed to surging crime, and others suggest they are unrelated. Here, we use data from California’s Bureau of State and County Corrections to assess Price’s impact on criminal prosecution. We observe that prosecutions dropped dramatically since Price took office, which suggests there is now diminished accountability for criminality in Alameda County.

On Feb 6, 2024, Governor Newsom announced the deployment of 120 CHP officers, along with air support and investigatory units, to bolster crime fighting in the City of Oakland. This was in response to Oakland’s unprecedented and ongoing rise in crime—a jump that occurred while crime rates dropped across California and the United States. Two days later, the Governor and Attorney General Bonta, sent in California State attorneys from the National Guard and Department of Justice to bolster criminal prosecution in Alameda County.

“An arrest isn’t enough. Justice demands that suspects are appropriately prosecuted. Whether it’s ‘bipping’ or carjacking, attempted murder or fentanyl trafficking, individuals must be held accountable for their crimes using the full and appropriate weight of the law.” — Governor Newsom

The next day, District Attorney Pamela Price announced refiling of charges, with gun and gang enhancements, against Hershel Hale and Shadihia Mitchell in the killing of a security guard Kevin Nishita in 2021.

This last announcement was particularly surprising because two months earlier, Price had dropped charges on those same defendants. In the new filing, she claimed to have surfaced new evidence justifying re-charging.

It was also surprising because Price has long pursued policies to divert criminals from incarceration and “disrupt the system”. Her policy directive in February 2023 included dropping the use of prior strikes, and prohibition of sentencing enhancements except for extraordinary circumstances and multiple levels of approval including Price’s. As noted by the Berkeley Scanner, Price also directs her staff to plea bargain for the lowest sentence regardless of the circumstances of the crime:

If a case is eligible for probation, that "shall be the presumptive offer," the directive reads. If it is not, the sentencing offer "shall be the low term."

Early actions in Price’s administration reinforce that the office has increased leniency for offenses, such as a plea deal to reduce murder charges which was rejected by the Alameda County Superior Court Judge as unjustified. Price herself notes in a interview with CBS on July 17:

Many times people who are perpetrators, are labeled as perpetrators, were actually victims. There's no bright line, certainly not in Alameda County, between someone who's a perpetrator and someone who's a victim.

Price added that her goal is to divert someone from the criminal justice system "anytime we can ... because the criminal justice system has been shown to be racially biased and undermining."

Price’s actions have raised the ire of many in the community, including victims advocates who initiated a recall campaign against her.

On the other hand, supporters of Price argue that she is an embattled and noble reformer being attacked with out-of-context anecdotes, lies, and misinformation at the hands of people with ulterior motives. And Price herself, in a recent interview with KQED, argued similarly, providing an array of additional defenses of her leadership and denying responsibility for the state of crime in Alameda County.1

Nevertheless, the influx of State attorneys, the exceptionally high crime in Oakland, and the ongoing controversies surrounding Price’s prosecutorial practices have rekindled long-standing questions:

What has been the impact of DA Price on prosecution of crime in Alameda County?

Are there rigorous data to back anyone’s claims?

And what is the impact on crime rates?

What is the District Attorney’s role in criminal prosecution?

When an adult is arrested, an officer takes them to county jail (Santa Rita Jail for Alameda County) where they are booked with a police report and evidence of probable cause. The defendant will be held in jail, with some exceptions, while the DA considers the evidence. The DA has 48 hours from booking to file charges (called a “complaint”) or the suspect is released.

If charges are filed, the defendant is arraigned (the first hearing with the judge) and may be held in jail while awaiting trial if they present a danger to the community or flight risk; or they may be released on bail at the determination of the judge.2 At this point, the case is considered “cleared” and it proceeds to trial or a plea bargain; or in some cases charges are dropped by the DA or dismissed by the judge. More than 97% of cases are resolved pre-trial. If convicted, the defendant is sentenced to prison, probation, or a diversion program in lieu of prison.

While the DA is instrumental throughout criminal prosecution, the decision to charge is entirely within the DA’s control. And charging is the necessary first step for state intervention; criminals cannot be held accountable, whether by incarceration or by alternative programs, without taking that first step. Thus, it is one of the most direct measures of how the DA’s policies and practices influence the delivery of justice.

How have charging decisions changed under Price?

The number of criminal complaints (criminal charges) filed by DAs across the State are tracked by the California Department of Justice. However, this data has not yet been released for 2023, and the DA’s office does not release it directly.

In lieu of Cal DoJ data, we use surrogate data from the Bureau of State and County Corrections (BSCC): the adult, non-sentenced jail population and bookings. The BSCC provides this data quarterly for all counties in California, and it has been updated through September 2023. The non-sentenced jail population is composed largely of individuals awaiting trial after arraignment (those that don’t post bail). Comparing changes in the jail population against bookings allow us assess charging activity by the DA.

As shown below, Alameda County’s jail population tracked with the State average3 until Pamela Price took office in 2023, and then it dropped to levels lower than that seen during COVID when incarcerated and jailed populations were released in mass. The precipitous drop in jail population during Price’s first nine months in office suggests that her office is charging fewer crimes than historical practice.

There is also a smaller, but still significant, drop in 2022 before Price took office (the 2022 full-year trend was a 22 person per month decrease, and the 2023 first-9-months trend was a 30 person per month decrease). Such declines are not unprecedented. In fact, the jail population has a 12-month historical cyclicality, with peak populations generally occurring in the first 2 months of the year (blue points), a trough in the summer, and a subsequent rebound in the second half of the year or the following year. But the Q1 peak never occurred in 2023, and the downward decline continued unabated.

There could also be other causes for the drop. For example, a common speculation is that police have arrested fewer people in 2023, despite the elevated crime rates within Alameda County. But BSCC data disprove this hypothesis. Bookings trended upward throughout 2023, ending the year with 5% more bookings per month than the start of year.

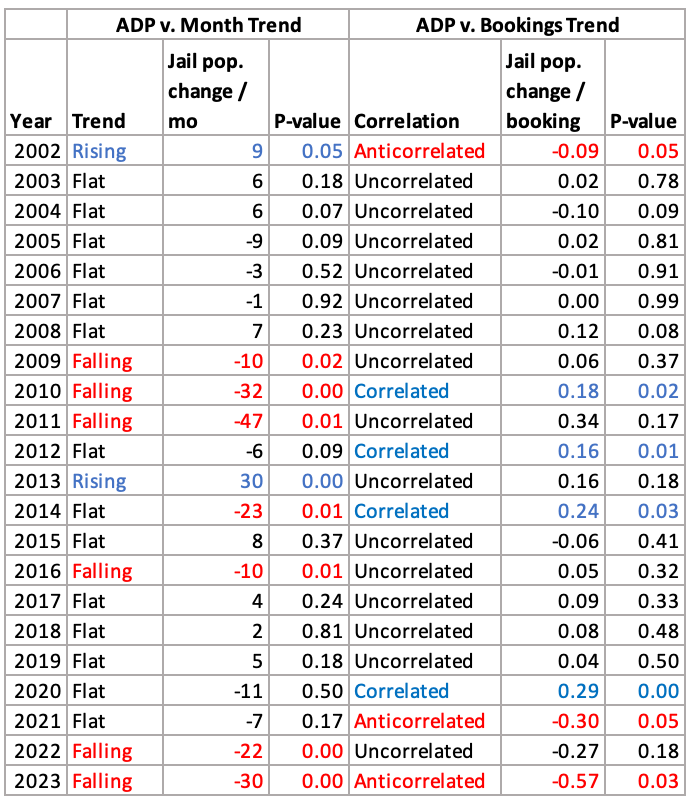

Thus, jail population moved opposite the bookings trend. In fact, 2023 was the only year in Alameda County in the past 20 years in which a falling jail population was significantly anti-correlated with bookings.4

In the Appendix, we also consider, and rule out, several other potential explanations for the drop in jail population, including random fluctuations, historical trends, general statewide variables impacting multiple counties, changes in state law, and changes in the speed of adjudication. None of these can explain Alameda County’s deep drop in non-sentenced jail population.

Almost certainly, Alameda County’s jail population dropped because the DA’s Office under Price has decided not to charge, or is not capable of charging, as many cases as were charged under previous DAs. This outcome is likely the result of Price’s substantive changes in prosecutorial practices and policies, as well as her removal or reassignment of dozens of experienced attorneys in the DA’s office.

Was crime impacted?

It is important to note that jailing individuals is not the objective of criminal justice. And we are not suggesting it should be the aim of the DA to increase the jail population. If anything, the objective is to minimize the non-sentenced jail population while preserving public safety and facilitating delivery of law enforcement, justice, and due process.5 But this should be achieved by improvements in the adjudication of cases, not a reduction in the rightful prosecution of crimes.

As shown here, the unusually large drop in jail population is not due to such improvements in the judicial process. Rather it appears to be the result of a dramatic decline in the charging of arrested individuals—at a time when crime and arrests have increased in Alameda County. The unusual deployment of California State attorneys to the County this month reinforces that conclusion.

For many residents, the opposing trends in prosecution and arrests is alarming; one would expect prosecutions to hold steady, if not increase, when bookings are increasing. And in San Francisco in 2023, this is what happened—the City saw a synchronous increase in both bookings and jail population during 2023, and crime dropped 7.5% overall.6

Naturally, this raises the question: do reduced prosecutions drive increased crime? We do not presently have the historical data nor prospective controlled studies in Alameda County to analyze this question analytically.

But we do note that the purpose of sentencing policy in the US includes accountability (punishment for harms), incapacitation (prevention of further harms), and rehabilitation. Certainly these objectives cannot be met if crimes are not prosecuted to the fair and full extent of the law. In particular, less prosecution of criminals means less incapacitation of their criminal activity, and less ability to target state resources toward rehabilitation.

Both logic and everyday evidence on the streets of Alameda County suggest that lax prosecution crime delivers neither public safety nor justice.

Appendix

Analysis of potential causes of jail population changes

Given the multiple factors that influence entry and exit from county jail, there could be other causes for the drop in jail population. We assess them here.

Hypothesis 1: the drop is just a chance occurrence due to natural fluctuations in jail population

It is clear from the figures above that jail populations fluctuate even under normal circumstances, and these fluctuations appear to be larger post-COVID than pre-COVID for Alameda County. So then is the drop in jail population simply a matter of random chance?

We address this question in the following chart which shows the drop is certainly not random—it falls to a level 5X below the 99% lower limit. According to historical fluctuations, the jail population should remain above the lower limit 99% of the time. The probability of a 5X departure happening by chance is 1 in 20 million.

Hypothesis 2: other counties are experiencing a similar drop as Alameda County

Although California shows no drop in jail population in 2023 on average, one might speculate that there are selected other counties that do see a drop. But across the 58 counties in California,7 only 6 showed a statistically significant downward trend in 2023, and only 2 of those dropped below their 99% limit (i.e., below the normal range expected from month-to-month variations); those were Alameda and Solano counties. Moreover, Alameda stands apart with the largest deviation from 2021-2022 average, and the only county whose drop was significantly anti-correlated with bookings.

Moreover, the fluctuations and trends exhibited in Santa Cruz and Solano—counties with the largest drops after Alameda—are consistent with their recent histories. Santa Cruz’s 2023 changes are within historical norms, and Solano’s 2023 change continues a steady 7-year historical decline. On the other hand, Alameda stands apart in that 2023 diverged entirely from historical pattern.

Hypothesis 3: The courts are adjudicating cases more quickly and therefore exiting defendants from jail faster.

It is possible that the court system dramatically accelerated the adjudication of cases in 2023, or the pretrial release process. In fact, Alameda County did implement a system in October 2022 aimed at accelerating release by 24 hours for 10% of the 74 persons booked each day. But this would result in reduction in the jail population by only 7 persons—about 2% of the 2023 decline in the non-sentenced jail population.8 And we found no other evidence that the Alameda Court system has accelerated the pace of trials in 2023.

Hypothesis 4: State law changes reduced jail holds or charging guidelines

Another possibility is that California criminal code may have changed in 2023, leading to fewer bookings resulting in jail time or charges. But of more than a dozen changes in 2023, only two of them reduce culpability for crimes, one concerning the prosecution of juveniles as adults, and one concerning drug use. The former could not explain the trend in Alameda County because the count of juveniles in custody dropped from 122 at the end 2022 to 116 at the end of 2023—a trend in the wrong direction and too small relative to the adult jail population drop of 360 persons. And the latter change in state law would have impacted counties statewide. But as noted above, Alameda County’s drop in jail population is not observed statewide.

Hypothesis 5: More lenient judges took office in 2023, resulting in expanded or accelerated granting of bail.

In 2023, there was only one new judge appointed to the criminal calendar out of 16 judges. Moreover, the number of unassigned slots on the calendar doubled from two in 2022 to four throughout 2023 (see January and October 2023 assignments). Thus even if the new judge was exceptionally lenient, the two additional vacancies would counter this impact, and slow the adjudication of cases. This would tend to increase jail population, not decrease it.

A Comment on the Sentenced Jail Population

The sentenced jail population was not the focus of the discussion here, because we focused on the non-sentenced population as a marker of criminal charging activity. But for completeness, we present below a chart comparing the two. It shows that the sentenced population is much smaller and has remained stable for the past few years (within normal range since the major release in 2020).

Notes

In the KQED interview, Price utilizes an array of common strategies to defend her performance as DA and to deflect responsibility for the state of crime in Alameda County. Key to markup below: Category in bold: Price’s position in normal font. (Time-stamps provided in parentheses)

Rome wasn’t built in a day: People should give change a chance (51:35)

False logic: “If locking people up was going to make us safer we’d be the safest country in the world.” (44:00)

It’s out of my control: Crime is not the impact of the DA, it’s a lot of other factors, particularly judges and law enforcement. (11:40)

Selective causality: The DA can’t control crime (11:40) or incarceration (16:30), but can impact human trafficking. (35:45)

Deference to authority: We are just following California’s guidelines (23:25).

It wasn’t my fault: We inherited an office “in crisis.” (03:44)

Victimhood / cut me some slack: No one criticized my predecessor during the rise in ghost guns and violence…but now there is a backlash against us who are trying to move the country forward. (49:35)

We are the hero fighting evil: For decades people had profited from a broken system and they didn’t like that change so they are resisting it. (5:10)

We don’t have enough resources or tools: We can’t report our charging rates like Chesa did because we don’t have the computer systems to track it. (17:45) We have terrible infrastructure. (04:05)

Misinformation: Police don’t bring juvenile defendants to the DA; only the probation officer decides what to do, and 99% of the time children are incarcerated. (19:20) (Author’s note: the DA or the Probation officer charges juvenile’s for crimes—this is called a “petition.” Also less than 50% of convicted juveniles are sent to juvenile hall. )

Conspiracy theory: The recall is a politically motivated process that is driven by few wealthy individuals, not the will of the people (5:10, 8:20, 51:20)

Eligibility considers the risk to public safety, the alleged crime committed, past failures to appear in court, criminal history, and numerous other factors.

San Bernardino County was excluded due to missing data in 2023.

Although pre-trial detention is paramount to ensure public safety and due process, research also suggests that it can have devastating implications for the lives of the detained. Many find it hard to keep a job, hard to keep their housing. Such outcomes make it more difficult to live a law-abiding life and could tip people into crime.

One County (Alpine) did not appear in the BSCC data set downloaded on February 8, 2024. Readers may download charts of bookings and jail population and control charts of the jail population for all California counties. (Control charts show the jail population relative to their historical 99% limits.)

There were 74 persons a month booked in Alameda County in 2022, of which about 7 are eligible for early release (release within 24 hours instead of waiting up to 48 hours for arraignment and/or release). Therefore, the early release population would be reduced from 14 people (7 persons/day * 2 days) to 7 people (7 persons/day * 1 day).

I write as a former career criminal trial prosecutor from Illinois. Price has reportedly commented that her goal is to divert someone from the criminal justice system anytime we can ... "because the criminal justice system has been shown to be racially biased and undermining." That was not my experience.

Price also is alleged to have directed her staff to plea bargain for the lowest sentence regardless of the circumstances of the crime: If a case is eligible for probation, that "shall be the presumptive offer," the directive reads. If it is not, the sentencing offer "shall be the low term."

If that directive is accurately quoted, it is not surprising that the crime rate in Oakland has risen dramatically under her tenure or that she faces criticism.

I would be interested to know who funded her campaign for office. I would be interested to know how many Alameda County prosecutors have left the office since Price assumed control prior to the arrival of the prosecutors the state has assigned to Alameda Co. I would be interested to know if my assumption is correct that these new additional prosecutor will be required to follow all of Price's prosecuting directives like the one quoted above.

Spectacular job! I hope the mainstream media starts adding some of this data to their articles. It's essential to have real data rather than guesswork and hunches.